Social impact

In response to international pressure, the Kimberley Process (KP) was established in 2003 to prevent conflict diamonds from entering into the legitimate diamond value chain. Today, KP facilitators claim 99.8 per cent of the world’s diamonds are conflict-free.

Yet, in a recent article published by The Financial Times, writer Henry Sanderson comments about critics claiming the term ‘conflict diamonds’ only covers diamonds mined by rebel groups and excludes those tied to other issues, such as human rights abuses, child labour, money laundering, or financing terrorism. In fact, IMPACT—one of the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that founded the Kimberley Process—left in 2017 due to the belief it was “giving buyers false confidence.”

Joanne Lebert, IMPACT’s executive director, said, “The Kimberley Process—and its certificate—has lost its legitimacy. The internal controls that governments conform to do not provide the evidence of traceability and due diligence needed to ensure a clean, conflict-free, and legal diamond supply chain.”

One alternative to the process is De Beers’ Diamond Blockchain Initiative, which digitally tracks the identity, ownership, contracts, and financing history of diamonds. As of now, De Beers can only track newly mined diamonds larger than two carats, although the company is working on ways of tracking existing inventory at the lower-carat ranges.

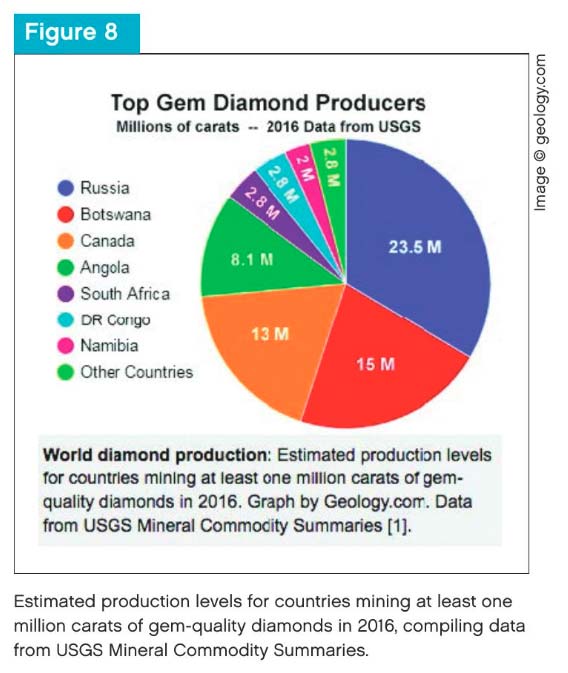

The social implications of diamond mining vary across geographic regions and are closely interlinked with governmental laws and regulations. For the most equitable assessment, I compared De Beers’ social impact in Botswana to its impact in Canada. These two countries come in second and third place in total diamond production worldwide (Figure 8).

Botswana

Although mining in Africa is often associated with conflict diamonds, Botswana is considered stable, democratic, peaceful, and of middle income. (For more, see “Botswana’s Success: Good Governance, Good Policies, and Good Luck” by M. Lewin in Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent.) From 1966 to 2014, its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita grew on average 5.9 per cent annually. (For more, read “Turning the Finite Resource into Enduring Opportunities,” produced by De Beers Group, Genesis Analytics, and PwC UK.) Debswana—a 50/50 joint venture between the government of Botswana and De Beers—generated US$4 billion in value to the economy in 2014, comprising approximately 25 per cent of Botswana’s GDP.

De Beers also supports local employment in the countries in which it operates, but the number of employees varies depending on the phase (e.g. high production, maintenance and care, etc.). In its 2016 Report to Society, the company lists figures regarding its commitment to increase diversity and its 15-year-old HIV/AIDS program, which offers care, medication, and support to employees and their families.

De Beers also supports local employment in the countries in which it operates, but the number of employees varies depending on the phase (e.g. high production, maintenance and care, etc.). In its 2016 Report to Society, the company lists figures regarding its commitment to increase diversity and its 15-year-old HIV/AIDS program, which offers care, medication, and support to employees and their families.

However, in the article “Flaws in Botswana’s Diamond Industry,” author Khadija Sharife, a South African investigative journalist, suggests the complex nature of the relationship between De Beers and the Botswana Democratic Party (DBP) undermines accountability and transparency. For example, she says De Beers has strategic ways to avoid taxes through imports and exports, and that the company determines the value of the diamonds on which the government levies taxes.

It is very difficult to determine the accuracy of these claims based on the information provided. However, in an effort to be more transparent, De Beers recruited auditor KPMG to oversee its 2016 Report to Society, in line with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

Canada

According to the World Bank, Canada is in 12th place globally for political stability. Mining activity is regulated by the federal and provincial governments as well as Aboriginal groups. Mining companies must adhere to specific tax laws, the Environmental Assessment Act, and other regulatory requirements.

De Beers’ relationship with the Canadian government is very different than with DBP. For instance, the Canadian government does not have a 15 per cent share in De Beers and half ownership of the mines. It also does not rely solely on diamond mines for economic growth, but also on other commodities.

In 2016, Ernst & Young published a report highlighting De Beers’ contribution to the Canadian economy. The Victor and Snap Lake mines have produced 13.5 million carats of rough, supplying $3.9 billion and $2.2 billion, respectively, to Canada’s gross value added (GVA). (For more, see De Beers Group’s Socio-economic Impact Report, produced by Ernst & Young in 2016.) Gahcho Kué, which opened in 2016, is said to have already brought $440 million to the Northwest Territories economy and is expected to add $5.7 billion to the territories’ GVA over its lifetime. (For more, see “The Socio-economic Impact of Gahcho Kué,” produced by De Beers Group and Ernst & Young in 2016.)

Along with the thousands of jobs it has created, De Beers supports 11 First Nations communities and has allotted $55 million through Impacts and Benefits Agreements (IBAs) to support inclusion and collaboration. Gem-quality lab-grown diamond-producing companies are not contributing to the economy and society on the same scale.

The takeaway

Lab-grown gem-quality diamond producers pose less of a threat to the environment than mining companies, as they use less freshwater, emit fewer greenhouse gases, and do not disrupt the land. However, they do not contribute to the economy and society as much as mining companies, and there is still the issue of transparency that needs to be addressed.

Extraction mining has long been associated with exploitation of resources and human rights abuses. However, at the end of the 20th century, mining companies—in coalition with government and nongovernment organizations—began pushing for more sustainable objectives. (For more, see F.P. Carvalho’s article, “Mining Industry and Sustainable Development: Time for Change,” published in Food and Energy Security in 2016.) Mining has made important contributions to economic growth, GDP, infrastructure development, and job creation worldwide. In other words, when it comes to evaluating the environmental and social impact of diamond mining, there is a trade-off between the economic and social benefits and the environmental costs.

Giselle Saati has been involved in the jewellery industry since childhood, as it is a family trade passed down for seven generations. She has worked full-time in the industry for a total of 11 years, and in areas including wholesale, retail, jewellery appraisals, and handmade jewellery. Before moving to Madrid to pursue her master’s studies, Saati worked at Harold Weinstein as a gemmologist and appraiser. She can be reached via e-mail at gisellesaati@gmail.com.

Giselle Saati has been involved in the jewellery industry since childhood, as it is a family trade passed down for seven generations. She has worked full-time in the industry for a total of 11 years, and in areas including wholesale, retail, jewellery appraisals, and handmade jewellery. Before moving to Madrid to pursue her master’s studies, Saati worked at Harold Weinstein as a gemmologist and appraiser. She can be reached via e-mail at gisellesaati@gmail.com.