Sustainable sparkle: The environmental impacts of mined versus lab-grown diamonds

by Samantha Ashenhurst | March 7, 2019 10:56 am

By Giselle Saati

[1]

[1]

The growing popularity of gem-quality lab-grown (also known as ‘synthetic’ or ‘cultured’) diamonds has caused a relentless marketing battle between diamond mining companies and gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers. Both contenders know corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives are key in appealing to the values of consumers. In 2015, an Annual Global Corporate Sustainability Report[2] from data measurement firm Nielsen indicated 66 per cent of consumers prefer to purchase products from socially responsible companies.

On the lab-grown producers’ side, companies such as Brilliant Earth, the Diamond Foundry, and Pure Grown Diamonds (PGD) market their diamonds as being conflict free and environmentally friendly. On the mining side, there is the Diamond Producers Association’s (DPA’s) ‘Real is Rare’ marketing campaign[3], which is intended to “promote the integrity and reputation” of natural diamonds.

Ali Saleem, a professor of energy and the environment at the University of Delaware, says “techniques for comparing synthetic and mined diamonds in terms of environmental impacts have yet to be refined.” (For more, refer to Saleem’s paper, “The Ecology of Diamond Sourcing: From Mined to Synthetic Gems as a Sustainable Transition,” published by Springer Science+Business Media New York in 2016.) Comparing the two types is complicated because there are several different factors to consider. First, diamond mining can take various forms, including open pit, closed pit, marine, and alluvial. The ecological footprint of mined diamonds also varies across geographic locations. Second, lab-grown diamonds are created through either high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) or chemical vapour deposition (CVD) processes, each of which has different energy usage.

There is also the problem of information asymmetry. Currently, access to information depends highly upon the company and location. However, most mining companies are expected to publish sustainability reports. Although this information could be biased, given the variability in how it is represented, the mining industry is regulated and in some cases employs third-party agencies to monitor environmental and social impacts. In the case of lab-grown producers, there is very little supervision and all companies are privately owned. As they are not obligated to disclose information, transparency is a concern.

Despite these complications, I have attempted to create greater objectivity concerning a matter about which there is not yet conclusive evidence. I have done this by devising criteria with which to evaluate both industries’ environmental and social impacts.

[4]

[4]

Energy use

Saleem mentions there are variations in energy use among mines and lab-grown producers depending on location. Beginning with lab-grown producers, to understand the energy used in creating lab-grown diamonds, one must examine the two methods employed—HPHT and CVD. HPHT is a process that converts carbon into a diamond through high pressure and temperature. CVD diamonds are created by using a microwave beam to deposit carbon-rich gas onto a silicon or diamond surface. (This information is derived from the synthetics and treatments portion of the Gemological Institute of America’s (GIA’s) ‘Diamonds & Diamond Grading’ course.)

According to Saleem, HPHT requires fewer ingredients and is faster, whereas CVD allows producers to grow diamonds over a larger surface and better control chemical impurities. It also does not require high temperature. Figure 1 shows the kilowatt hours per carat (kWh/ct.) of two gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers—Apollo Diamond and Gemesis—as well as some details of the production process. However, it is important to note both these companies have been acquired or renamed and current information could be very different.

In an interview, John Hassard, owner of Edgecombe Abrasives (a company that supplies industrial equipment using lab-grown diamonds), explained the variations in energy use between HPHT and CVD depend on several variables, including type of product, yield, grades and applications, type of HPHT press (cubic versus belt), and type of reactors. Both processes require uninterrupted power sources for their production cycles, which can take anywhere from 30 minutes to several days, depending on the target product. HPHT can produce more diamonds per cycle, but with CVD, you can control the quality of the product, which is important for diamonds used in jewellery. Scalability and purity are the major contributors to energy use in lab-grown diamond production. High quality or purity utilizes more energy and is costly.

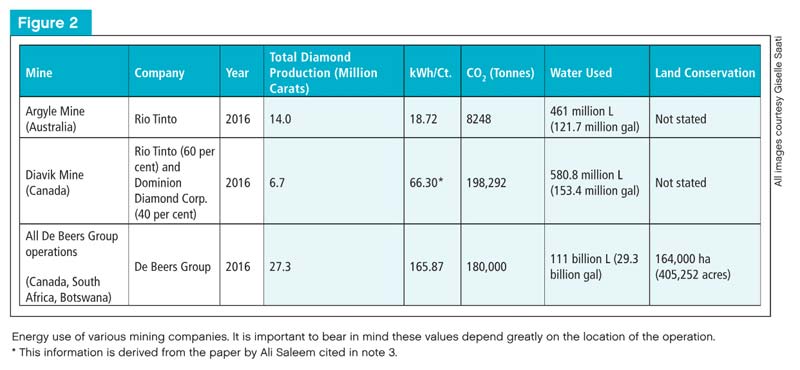

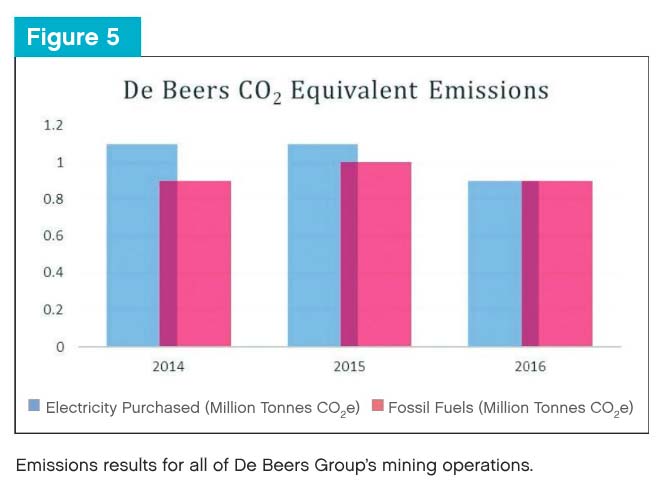

Figure 2 shows the kWh/ct. of certain mining companies. There are two important factors to note. First, this value varies greatly depending on location—the Argyle mine in Australia uses 6.7 to 18.72 kWh/ct., while the Diavik mine uses 66.30 kWh/ct. One reason for this, as Saleem points out, is the fact most Canadian diamond mines are found in remote locations in the Northwest Territories and thus need to produce electricity from diesel fuel. Currently, 77 per cent of De Beers’ energy comes from fossil fuels, a number it aims to reduce using wind farms. (For more, see De Beers Group’s Socio-economic Impact Report, produced by Ernst & Young in 2016.) However, although wind farms are a great source of renewable energy, they pose a threat to wildlife such as bats and birds.

The second important factor is the quantity of carats produced. Mining companies produce millions of carats per year, well outpacing lab-grown diamond producers. Also, it takes days and even weeks to produce larger-carat lab-grown diamonds. There is no data available on the quantity of diamonds lab-grown producers are creating overall, but the Diamond Foundry says[5] it produces 100,000 carats per year, which is significantly less than diamond mines. This begs the question: if lab-grown diamond producers were to pump out the same quantity of diamonds as mining companies, would they be as energy efficient? Could they possibly match or surpass the amount of energy diamond mining companies are using? The issue of transparency and the quantity of diamonds produced could change lab-grown diamond producers’ positive image.

[6]

[6]

Greenhouse gas emissions

[7]

[7]

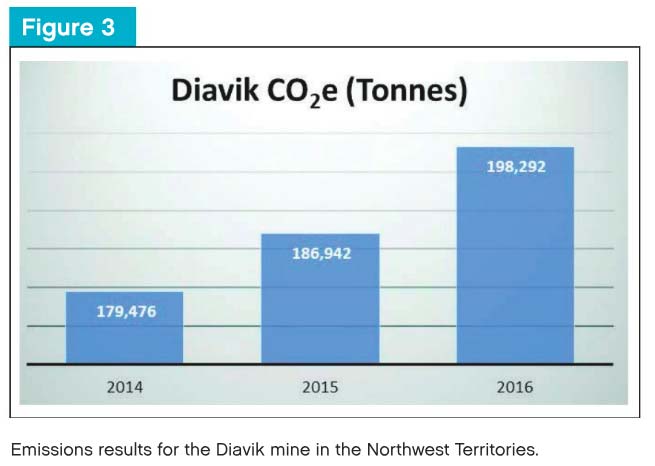

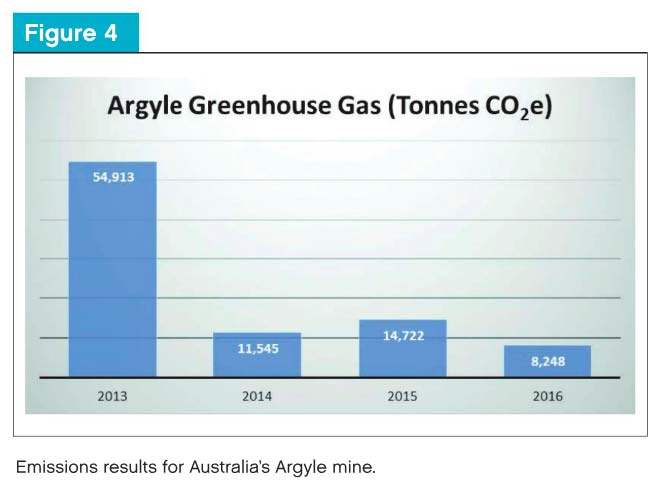

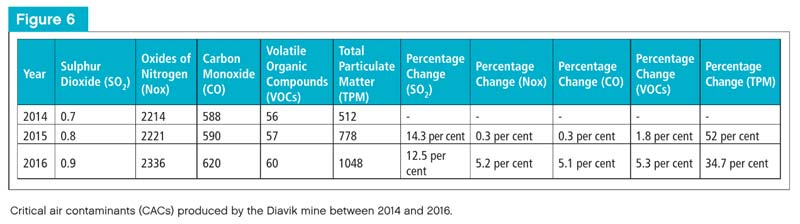

It is obvious diamond mining companies fall short in the emissions category. Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the emissions results of the Diavik mine, the Argyle mine, and De Beers Group’s operations. Between 2015 and 2016, Diavik’s emissions grew by 6.07 per cent whereas Argyle’s decreased by 44 per cent. De Beers stayed relatively steady, but it also has a larger portfolio of mines. Further, over the past three years, the Diavik mine has increased its critical air contaminants (CACs), which affect air quality, plants, and both human and animal respiratory systems (Figure 6).

In 2017, De Beers announced Project Minera, an effort to become carbon-neutral[8] by storing large volumes of carbon in kimberlite tailings (the residual material left after diamonds have been extracted). This is a natural process, as kimberlite has properties for storing carbon. The risks and uncertainties have yet to be ironed out, but as Bruce Cleaver, CEO of De Beers, aptly puts it[9], “This project could play a major role in changing the way not only the diamond industry, but also the broader mining industry addresses the challenge of reducing its carbon footprint.”

Although lab-grown diamond producers do not share their GHG emissions, it is highly unlikely they are contributing the same amount as diamond mining companies, as the latter need fuel for transportation, operating large machines, and running large facilities. Currently, the Diamond Foundry is the only lab-grown diamond producer certified[10] as fully carbon neutral.

[11]Unfortunately, without sufficient evidence, it is very difficult to establish an accurate carbon footprint. Further, lab-grown producers are not disclosing which metal alloys they utilize to make their diamonds. Many also do not mention the fact CVD diamonds need a seed diamond (natural or lab-grown) in order to be grown. (Click here[12] to read R. Linares’ piece, “CVD-grown Synthetic Diamonds, Part 1.”) These mined metal alloys and extra diamonds should be factored into the assessment.

[11]Unfortunately, without sufficient evidence, it is very difficult to establish an accurate carbon footprint. Further, lab-grown producers are not disclosing which metal alloys they utilize to make their diamonds. Many also do not mention the fact CVD diamonds need a seed diamond (natural or lab-grown) in order to be grown. (Click here[12] to read R. Linares’ piece, “CVD-grown Synthetic Diamonds, Part 1.”) These mined metal alloys and extra diamonds should be factored into the assessment.

Water use

Water is one of the most precious resources for diamond miners. It is important not only for the health of mine workers, but also for processing. (This information comes from the diamond mining section of GIA’s ‘Diamonds & Diamond Grading’ course.)

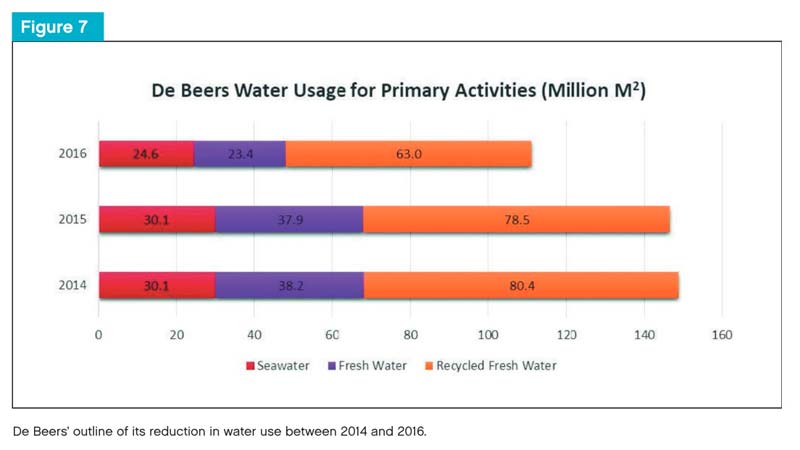

In 2016, South Africa experienced a severe drought, requiring De Beers—which operates several mines in that country—to focus on water reduction. The company’s subsidiary Element Six launched Diamox, a system that treats highly contaminated industrial wastewater by using lab-grown industrial diamonds to remove dissolved pollutants. (For more, For more, see De Beers Group’s Socio-economic Impact Report, produced by Ernst & Young in 2016.) The process is electrochemical, making it highly effective and sustainable. It is even safe to put the water back into the environment after treatment. In De Beers’ 2016 Report to Society, the company outlined its reduction in water use over the past three years (Figure 7).

Another major water-related issue stemming from diamond mining is dewatering of Canadian lakes. In the Northwest Territories, many kimberlite pipes are found at the bottom of lakes. Diamond miners operating in Canada must take special precautions in conserving fish and other species, as well as monitoring biodiversity where they mine.

[13]Both CVD and HPHT lab-grown diamond producers use freshwater in their processes. In an interview with this author, Dean VandenBiesen, vice-president of LifeGem, said water circulates in his company’s chiller systems to keep the machines from overheating. VandenBiesen described this as a closed system that does not allow measurement of the water used. Similarly, a representative of the Diamond Foundry indicated the company uses 7.5 to 113 L (2 to 30 gal) of freshwater per carat, which is approximately one shower’s worth per carat. Overall, gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers consume considerably less water than mining companies.

[13]Both CVD and HPHT lab-grown diamond producers use freshwater in their processes. In an interview with this author, Dean VandenBiesen, vice-president of LifeGem, said water circulates in his company’s chiller systems to keep the machines from overheating. VandenBiesen described this as a closed system that does not allow measurement of the water used. Similarly, a representative of the Diamond Foundry indicated the company uses 7.5 to 113 L (2 to 30 gal) of freshwater per carat, which is approximately one shower’s worth per carat. Overall, gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers consume considerably less water than mining companies.

Land conservation and biodiversity

There is no question ‘team lab-grown’ wins the land conservation and biodiversity category. All forms of mining leave an environmental footprint, which sometimes cannot be remediated. However, it is worth mentioning mining companies’ efforts to restore the land and ecosystems they affect.

In Canada, many mining companies are required to work with third-party environmental groups to assess their impact on the ecosystem. For instance, Diavik has the Environmental Monitoring Advisory Board[14] (EMAB) to monitor specific biodiversity concerns, such as water and air quality and impact on fish, mammals, and birds.

De Beers’ Victor mine is undergoing a progressive reclamation process[15] that began in 2014. Last year, De Beers spent $4.2 million on land conservation at Victor, and this year it plans to also spend another $7.2 million. The process involves planting 477,110 trees of different varieties, all of which are native to northern Ontario’s ecosystem.

[16]

[16]

[17]

[17]

Social impact

In response to international pressure, the Kimberley Process (KP) was established in 2003 to prevent conflict diamonds from entering into the legitimate diamond value chain. Today, KP facilitators claim 99.8 per cent of the world’s diamonds are conflict-free.

Yet, in a recent article published by The Financial Times, writer Henry Sanderson comments about critics claiming the term ‘conflict diamonds’ only covers diamonds mined by rebel groups and excludes those tied to other issues, such as human rights abuses, child labour, money laundering, or financing terrorism. In fact, IMPACT—one of the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that founded the Kimberley Process—left in 2017 due to the belief it was “giving buyers false confidence.”

Joanne Lebert, IMPACT’s executive director, said, “The Kimberley Process—and its certificate—has lost its legitimacy. The internal controls that governments conform to do not provide the evidence of traceability and due diligence[18] needed to ensure a clean, conflict-free, and legal diamond supply chain.”

One alternative to the process is De Beers’ Diamond Blockchain Initiative[19], which digitally tracks the identity, ownership, contracts, and financing history of diamonds. As of now, De Beers can only track newly mined diamonds larger than two carats, although the company is working on ways of tracking existing inventory at the lower-carat ranges.

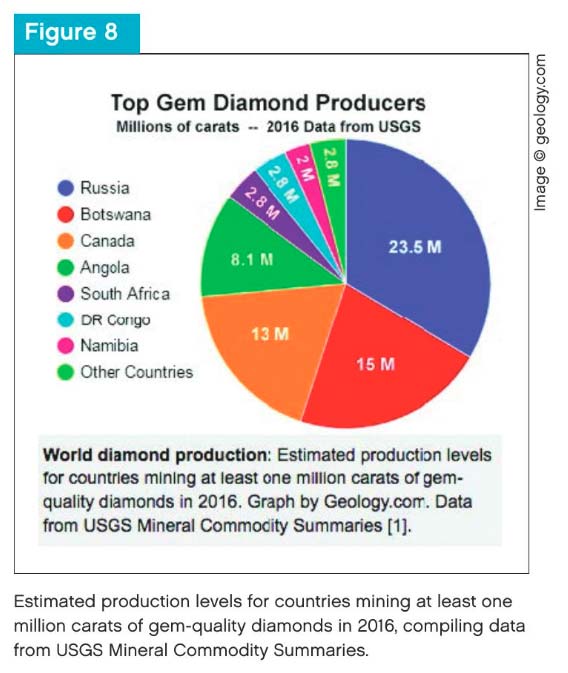

The social implications of diamond mining vary across geographic regions and are closely interlinked with governmental laws and regulations. For the most equitable assessment, I compared De Beers’ social impact in Botswana to its impact in Canada. These two countries come in second and third place in total diamond production worldwide (Figure 8).

Botswana

Although mining in Africa is often associated with conflict diamonds, Botswana is considered stable, democratic, peaceful, and of middle income. (For more, see “Botswana’s Success: Good Governance, Good Policies, and Good Luck” by M. Lewin in Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent.) From 1966 to 2014, its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita grew on average 5.9 per cent annually. (For more, read “Turning the Finite Resource into Enduring Opportunities,” produced by De Beers Group, Genesis Analytics, and PwC UK.) Debswana—a 50/50 joint venture between the government of Botswana and De Beers—generated US$4 billion in value to the economy in 2014, comprising approximately 25 per cent of Botswana’s GDP.

[20]De Beers also supports local employment in the countries in which it operates, but the number of employees varies depending on the phase (e.g. high production, maintenance and care, etc.). In its 2016 Report to Society, the company lists figures regarding its commitment to increase diversity and its 15-year-old HIV/AIDS program, which offers care, medication, and support to employees and their families.

[20]De Beers also supports local employment in the countries in which it operates, but the number of employees varies depending on the phase (e.g. high production, maintenance and care, etc.). In its 2016 Report to Society, the company lists figures regarding its commitment to increase diversity and its 15-year-old HIV/AIDS program, which offers care, medication, and support to employees and their families.

However, in the article “Flaws in Botswana’s Diamond Industry,” author Khadija Sharife, a South African investigative journalist, suggests the complex nature of the relationship between De Beers and the Botswana Democratic Party (DBP) undermines accountability and transparency. For example, she says De Beers has strategic ways to avoid taxes through imports and exports, and that the company determines the value of the diamonds on which the government levies taxes.

It is very difficult to determine the accuracy of these claims based on the information provided. However, in an effort to be more transparent, De Beers recruited auditor KPMG to oversee its 2016 Report to Society, in line with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

Canada

According to the World Bank, Canada is in 12th place[21] globally for political stability. Mining activity is regulated[22] by the federal and provincial governments as well as Aboriginal groups. Mining companies must adhere to specific tax laws, the Environmental Assessment Act, and other regulatory requirements.

De Beers’ relationship with the Canadian government is very different than with DBP. For instance, the Canadian government does not have a 15 per cent share in De Beers and half ownership of the mines. It also does not rely solely on diamond mines for economic growth, but also on other commodities.

In 2016, Ernst & Young published a report highlighting De Beers’ contribution to the Canadian economy. The Victor and Snap Lake mines have produced 13.5 million carats of rough, supplying $3.9 billion and $2.2 billion, respectively, to Canada’s gross value added (GVA). (For more, see De Beers Group’s Socio-economic Impact Report, produced by Ernst & Young in 2016.) Gahcho Kué, which opened in 2016, is said to have already brought $440 million to the Northwest Territories economy and is expected to add $5.7 billion to the territories’ GVA over its lifetime. (For more, see “The Socio-economic Impact of Gahcho Kué,” produced by De Beers Group and Ernst & Young in 2016.)

Along with the thousands of jobs it has created, De Beers supports 11 First Nations communities and has allotted $55 million through Impacts and Benefits Agreements (IBAs) to support inclusion and collaboration[23]. Gem-quality lab-grown diamond-producing companies are not contributing to the economy and society on the same scale.

The takeaway

Lab-grown gem-quality diamond producers pose less of a threat to the environment than mining companies, as they use less freshwater, emit fewer greenhouse gases, and do not disrupt the land. However, they do not contribute to the economy and society as much as mining companies, and there is still the issue of transparency that needs to be addressed.

Extraction mining has long been associated with exploitation of resources and human rights abuses. However, at the end of the 20th century, mining companies—in coalition with government and nongovernment organizations—began pushing for more sustainable objectives. (For more, see F.P. Carvalho’s article, “Mining Industry and Sustainable Development: Time for Change,” published in Food and Energy Security in 2016.) Mining has made important contributions to economic growth, GDP, infrastructure development, and job creation worldwide. In other words, when it comes to evaluating the environmental and social impact of diamond mining, there is a trade-off between the economic and social benefits and the environmental costs.

[24]Giselle Saati has been involved in the jewellery industry since childhood, as it is a family trade passed down for seven generations. She has worked full-time in the industry for a total of 11 years, and in areas including wholesale, retail, jewellery appraisals, and handmade jewellery. Before moving to Madrid to pursue her master’s studies, Saati worked at Harold Weinstein as a gemmologist and appraiser. She can be reached via e-mail at gisellesaati@gmail.com[25].

[24]Giselle Saati has been involved in the jewellery industry since childhood, as it is a family trade passed down for seven generations. She has worked full-time in the industry for a total of 11 years, and in areas including wholesale, retail, jewellery appraisals, and handmade jewellery. Before moving to Madrid to pursue her master’s studies, Saati worked at Harold Weinstein as a gemmologist and appraiser. She can be reached via e-mail at gisellesaati@gmail.com[25].

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Sparkle-Opener.jpg

- an Annual Global Corporate Sustainability Report: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahlandrum/2017/03/17/millennials-driving-brands-to-practice-socially-responsible-marketing/#3ea56d754990

- ‘Real is Rare’ marketing campaign: https://diamondproducers.com/about-dpa/mission-statement/

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig1.jpg

- the Diamond Foundry says: https://diamondfoundry.com/blogs/the-foundry-journal/new-foundry-opened-in-san-francisco

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig3_2.jpg

- an effort to become carbon-neutral: http://www.mining.com/web/de-beers-pioneers-research-programme-make-carbon-neutral-mining-reality/

- aptly puts it: https://af.reuters.com/article/africaTech/idAFL8N1I62DB

- the only lab-grown diamond producer certified: https://diamondfoundry.com/blogs/the-foundry-journal/new-foundry-opened-in-san-francisco

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig4.jpg

- here: https://www.gia.edu/news-research-CVD-grown-part1

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig5_2.jpg

- the Environmental Monitoring Advisory Board: https://www.emab.ca/priorities

- is undergoing a progressive reclamation process: https://www.debeersgroup.com/media/company-news/2018/one-third-of-victor-mine-footprint-to-be-reclaimed-by-year-end.aspx

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig6-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig7_2-1.jpg

- do not provide the evidence of traceability and due diligence: http://www.jckonline.com/editorial-article/another-ngo-leaves-kimberley-process

- De Beers’ Diamond Blockchain Initiative: https://www.diamonds.net/News/NewsItem.aspx?ArticleID=59932&ArticleTitle=De+Beers+Is+the+New+Kid+on+the+Blockchain

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/fig8_2.jpg

- Canada is in 12th place: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_political_stability/

- is regulated: https://iclg.com/practice-areas/mining-laws-and-regulations/canada#chaptercontent15

- to support inclusion and collaboration: http://www.canadianminingjournal.com/news/diamonds-gahcho-kue-to-pump-6-7b-to-nwt-economy/

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Saati_headshot.jpg

- gisellesaati@gmail.com: mailto:gisellesaati@gmail.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/sustainable-sparkle-the-environmental-impacts-of-mined-versus-lab-grown-diamonds/