The ‘alloyed’ truth: Using the right mix for the job

Refining the art of alloying

Pure gold and silver are generally too soft for most jewellery applications. As such, alloying gold with silver and silver with copper proved to create harder and more durable blends.

Sterling silver—which is 92.5 per cent pure silver and 7.5 per cent copper—has been the defacto standard alloy for centuries for use in currency, jewellery, and hollowware. It is a lustrous white metal, but tarnishes due to sulfur compounds in the environment. This can be used to advantage when silver items are patinated to add depth and interest to a complex design, but it is less desirable if you wish the metal to remain white. Sterling is also prone to firescale when being soldered—unless care is taken to prevent this, finishing silver pieces can be a lot of work. New alloys of sterling and others of higher purity have been on the market for a few years. These propriety patented alloys combine good workability with superior white colour, along with the great benefit of reduced firescale and a high degree of anti-tarnish properties. The ‘secret’ ingredients in these alloys are small percentages of elements, such as germanium, platinum, and palladium.Â

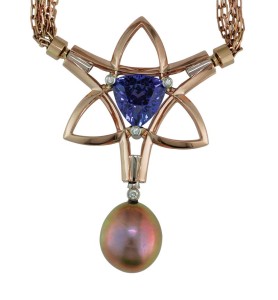

For many centuries, jewellers had only gold and silver with which to work. By the mid- to late-18th century, platinum began to replace silver in the crafting of fine jewellery, as methods for working with it were developed. It wasn’t until 1815 that Russian metallurgist/jewellers mixed 75 per cent gold with 25 per cent copper to make 18-karat rose gold, while it took another 100 years for jewellers in Pforzheim, Germany, to develop the first commercially produced white gold alloys.

With platinum’s primary use as a strategic metal in industrial and military applications around the Second World War, white gold gained in popularity, taking its place in all but very high-end jewellery. Only the relatively recent demand achieved by the efforts of the Platinum Guild International (PGI)—and some would argue designer Scott Kay—has returned the metal to its rightful place.Â

It is not easy to ‘bleach’ the yellow colour from pure gold and still end up with an alloy approaching platinum’s or silver’s whiteness. The first (and still most common) method is to add nickel to gold. Unfortunately, these two metals are not particularly compatible and the first alloys, although much harder than platinum, were also extremely brittle. Adding small amounts of other metals to the mix improved workability, but the resulting colour was not very white. Brownish and yellowish ‘warm’ shades were not very attractive and the only real solution was to electroplate this not quite white gold with rhodium. Of course, electroplating is only skin deep; depending on the type of jewellery and frequency of wear, it needs to be re-applied periodically.Â