In conversation with Justin K. Prim

By Lauriane Lognay

Photos courtesy Justin K. Prim

History in on itself is a massive subject—indeed, it is so immense, one might assume every theme or invention in the world has its own recorded history, documented in books for others to discover. What do we know about the people behind the writing of these texts, though? What of the individuals who made the decision to study a specific niche, topic and educate others about it?

The art of lapidary has existed for centuries. The jewellery and gemstone industry has seen hundreds of books published, detailing techniques, diagrams, and historical jewellery. Within this specific discipline, though, next to no one has gone as far and deep into research as Justin K. Prim.

I first met Justin at a gemmology conference years ago. Off the bat, I knew we shared the same passions—namely, learning and gemstones. So, when an opportunity presented itself in the form of him coming to Canada to teach some faceting classes, I jumped at the chance to speak to him to learn more about his gemstone journey.

Tell us a bit about yourself

Justin K. Prim (JKP): I’m a gem-cutter from Chicago. For most of my young life and into my 20s, I was an artist of some sort. I tried all sorts of things—I was a musician, an audio engineer, a graphic designer, a video editor, an artistic sewer, and a backpack maker. As I approached 30, I decided to move to San Francisco and remake my life, abandoning my previous major artistic endeavours and staying open to whatever new opportunities might cross my path.

I don’t know if it was destiny or luck, but the first friend I made in San Francisco was a mineral dealer. When I went to her house, she had crystals and minerals everywhere. I had a rock collection as a kid, and seeing those minerals sparked some kind of joy and curiosity inside me. A few months later, she took me to my first gem fair. I had never seen faceted gemstones before. Jewellery was an alien world to me at that time, but I became very curious about how people could cut such tiny and precise stones.

To make a long story short, I discovered there was a lapidary club in my neighbourhood, and I immediately became a member. Learning to cut gemstones changed my life and was the artistic avenue I was looking for that would allow me to make money and also be creative. The rest, as they say, is history.

How did you come to be a lapidary historian?

JKP: After three years of being a member of the lapidary club in San Francisco, I decided to get serious about what I was doing. I needed to know more about gems and realized gemmology school was the quickest way to go.

I enrolled in Gemological Institute of America (GIA) and moved to the United Kingdom and, later, Bangkok to complete my courses. I love to travel, so it was fun to do my gemmology classes around the world instead of staying in California.

I arrived in Bangkok wanting to learn faceting techniques from local Thai cutters and discover more about the history of the craft I was doing, but came to a dead end on both accounts. I couldn’t find any cutters to learn from in Bangkok, and the only book I found on the history of gem-cutting read more like a Wikipedia article than the deep dive I was craving.

In 2017, I decided to take it upon myself to write the book I was looking for. Five years later, I’ve done extensive research in France, England, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Switzerland, and the United States. I’ve published several in-depth articles on the history of faceting in different parts of the world, and I’m currently working on several books exploring the gem-cutting cultures of Europe and America. I’ve become absolutely obsessed with this project. It’s extremely satisfying to collect all of these historical puzzle pieces from sources all over the world, then slowly assemble them to understand how faceting started and how it has evolved in the Middle East, Europe, and North America, and in the cutting centres of Asia and South America.

Has lapidary reached its limit in terms of technique and creative potential?

JKP: This is a complicated question and there are a few sides to it. There will always be a demand for faceted stones and cabochons from the jewellery industry; the question of who will fulfil this demand remains unknown.

If we look at the historical localities for high-end stone cutting—Paris, London, Idar-Oberstein, and Geneva—there are only a few cutters left in each of these cities, and the cost of labour has made these hubs nearly obsolete for today’s jewellery manufacturing pipeline. Much of the work of the Old World has been moved to cheaper labour centres, such as Thailand, India, and Sri Lanka. The stones being cut in Asia are stylistically very similar to the classic designs formerly done in Europe. I don’t see much innovation coming out of these places, though; it’s primarily order fulfilment.

Surprisingly, most of the innovation we are seeing is happening in the amateur world with hobby cutters in North America, as well as a bit in Australia, the U.K., and Europe. Since the late 1990s, we’ve seen the development of all types of new cutting styles, including concave cutting, as well as new hybrid techniques that mix traditional flat faceting, concave faceting, and carving. There are some incredible gemstone artists right now who are doing mind-blowing work that looks like it comes from a completely different universe as compared to the more traditional cuts.

Lapidary is definitely in a transitional phase. The jewellery trade hasn’t yet incorporated much of the new cutting styles into mass production. Even through concave faceting is more than 20 years old, it’s still on the fringe of the commercial jewellery world. There are small boutique jewellers who create work around these innovative gems, but they are targeting very niche markets. I think we are still a long way away from seeing concave stones in the windows of big brands on the high streets of America and Europe. As an art form, there’s more to be done by future generations of gem-cutters, but from a commercial point of view, traditional esthetics still reign supreme when it comes to high-end jewellery.

What are the earliest traces of gemstone cutting?

JKP: If we are talking about any type of gemstone manipulation, the practice is extremely old. Some of the earliest bead necklaces, which are made from shells with holes drilled in them, go back about 100,000 years—by comparison, farming is only about 12,000 years old. We can find cabochons in ancient Egyptian jewellery dating back almost 4000 years. I hope to find even older examples as my research continues.

The art of faceting started at the beginning of the European Renaissance in the late 1300s. For me, this is when it gets very interesting, as faceting is a lot more complicated than cutting cabs. Cutters need very specific tools and technology to be able to create their gems. I find the story of gem-cutting technology to be a great analogy for the technological achievement of humans in general. If we chart our progress from the 1400s until now, everything we take for granted today was developed during this time—from the birth of science itself, to optics, mineralogy, manufacturing, electricity, global logistics, cell phones, the internet, and so forth. Every development we have made as a species has a reflection in the art and science of cutting gems. As the human race develops, so, too, does the art of cutting. Today, we have very sophisticated and well-engineered machines to help us facet a gemstone, but we wouldn’t have them if we didn’t have every technological step along the way, which made their innovation and production possible. This is an incredibly rich history that says just as much about the human race as it does about gems and jewellery, which is why it has been an easy rabbit hole to fall down as a researcher and writer.

What makes a good lapidary artist/faceter?

JKP: For me, there has to be a balance between artist expression and an understanding of gemmological sciences. There also needs to be a balance between creativity and commercial practicality.

At the end of the day, a gemstone needs to go into a piece of jewellery. As cutters, we must maximize the beauty of the stone, but also be conscious of its weight loss, along with the time it takes to cut it. If you make an extremely beautiful stone, but it takes a month to cut, it will be very hard for a jeweller or end-customer to justify the labour cost. On the flip side, if you can cut a stone in 30 minutes but it is not beautiful, the labour cost will be low, but it’s unlikely anyone will want to buy the product. Everything must be in balance.

You must know your stones. You must know your tools. You must know the tastes of your customers. You must know yourself, as the craftsperson. If all of these things are well developed, you can, in a day or less, take a rough or poorly cut stone and transform it into something beautiful. In this situation, everyone is happy, and everyone makes money. The stone can be sold to a customer who will cherish its beauty, but also feel comfortable with its cost.

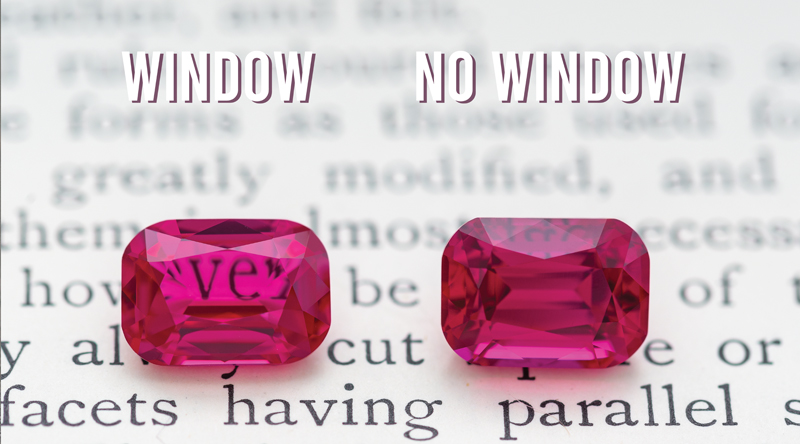

What is the added value of a bespoke-cut gem?

JKP: Simply put, the added value can be found in a bespoke-cut gem’s style and cutting quality. Commercial cutters are usually trained in the classic cutting styles. As such, if one is looking for an innovative shape or design, they are looking for a bespoke cutter. Further, commercial cutters are not traditionally trained in gemmology. They tend to use archaic cutting tools and, as such, aren’t always able to cut stones at appropriate angles. This is why so many gems in the trade are poorly cut and show windows that leak light and colour.

Like any art form, it’s very tricky to compare styles between cutters. There will always be someone who likes one more than the other, and not everyone will agree. The historical research I have done has opened my eyes to the tastes of old Europe. Likewise, continued conversations with today’s jewellers offer some insight into new preferences developing across America and beyond. Notably, North American customers are asking for (and buying) flashier, more brilliant styles, while mixed-cut stones are favoured in Europe.

The better the cutter, the better the quality, which translates to a fully saturated and sparkling gem with no window, good polish, good meet-points, an attractive shape, and good proportions.

Who can become a lapidary artist?

JKP: Anyone with a creative eye and a passion for gems can become a gem-cutter. The process itself, though, is usually quiet and meditative. For some people, the idea of sitting for long hours making tiny, careful changes to small stone is not ideal.

While on my own cutting journey, I started a school to teach faceting, and we have trained about 75 students in the past few years. The best students to emerge from our course are open-minded, flexible, attentive to details, and usually have an entrepreneurial spirit. It is unlikely to get hired as a gem-cutter, so, usually, these professionals have to go into business for themselves, which is a fair of amount of work. A successful gem-cutting practice requires a lot more than good cutting—you also need to be a good photographer, a confident salesperson, and a strong writer. It requires a keen understanding about price negotiation, customer service, communication, time management, shipping, and more. It takes a lot of discipline and effort to create a successful gem-cutting business, but, once you’ve mastered all those skills, you are not only a better businessperson but also a more well-rounded human. It’s worth it.

A final word?

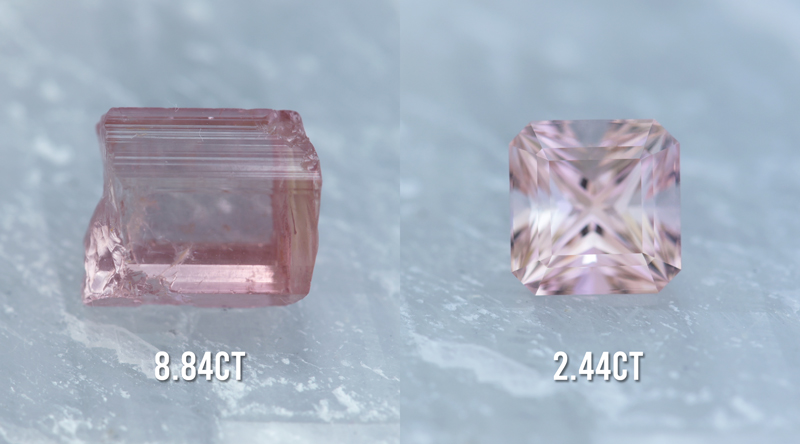

JKP: The power of the gem-cutter is often underappreciated. When looking at a rough gem, it’s the cutter who decides how the final stone looks, how colourful it will be, what the final hue is, how sparkly it will be, and how much it weighs. All the things we cherish in faceted, coloured stones are the result of cutting. The lapidary is a true magician who is able to look at pure potential in a rough and turn it into a beautiful product that is able to be sold on its own or set in jewellery, which will be cherished for generations to come.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA), and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana Inc., a Montréal-based company working in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached at rippanainfo@gmail.com.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA), and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana Inc., a Montréal-based company working in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached at rippanainfo@gmail.com.