The name game: Is origin the deciding factor?

You name it

The Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC) defines paraiba tourmaline as blue (i.e. neon blue or violet), bluish-green to greenish-blue, or green elbaite tourmaline containing copper and manganese, similar to the material that was originally mined in Paraiba, Brazil, although not necessarily originating there. As such, LMHC labs describe paraiba tourmaline on their reports using the following terminology regardless of geographic origin:

- Species: elbaite

- Variety: paraiba tourmaline

- Origin: origin determination is optional.

This is consistent with CIBJO, which defines paraiba tourmaline as having a “green to blue colour caused by copper.” Since it makes no mention of origin, CIBJO also considers paraiba tourmaline to be a general variety. In contrast, the American Gemological Laboratories (AGL) describes copper-bearing tourmaline from Mozambique or Nigeria as ‘paraiba-type.’ CIBJO and LMHC are the only two organizations I have found in my research that use paraiba tourmaline as a variety name for African cuprian tourmaline.

Some gemmologists believe lab reports should simply describe the stone and leave trade names to a company’s marketing department. At our lab, we avoid using paraiba tourmaline to designate variety on our reports, and instead indicate ‘cuprian tourmaline’ when copper is present. In my opinion, including a qualifying statement in the report’s comment section along the lines of “Known in the trade as paraiba tourmaline” when referring to neon blue-green tourmaline is acceptable. This is also the practice of labs like the German Foundation for Gemstone Research (DSEF).

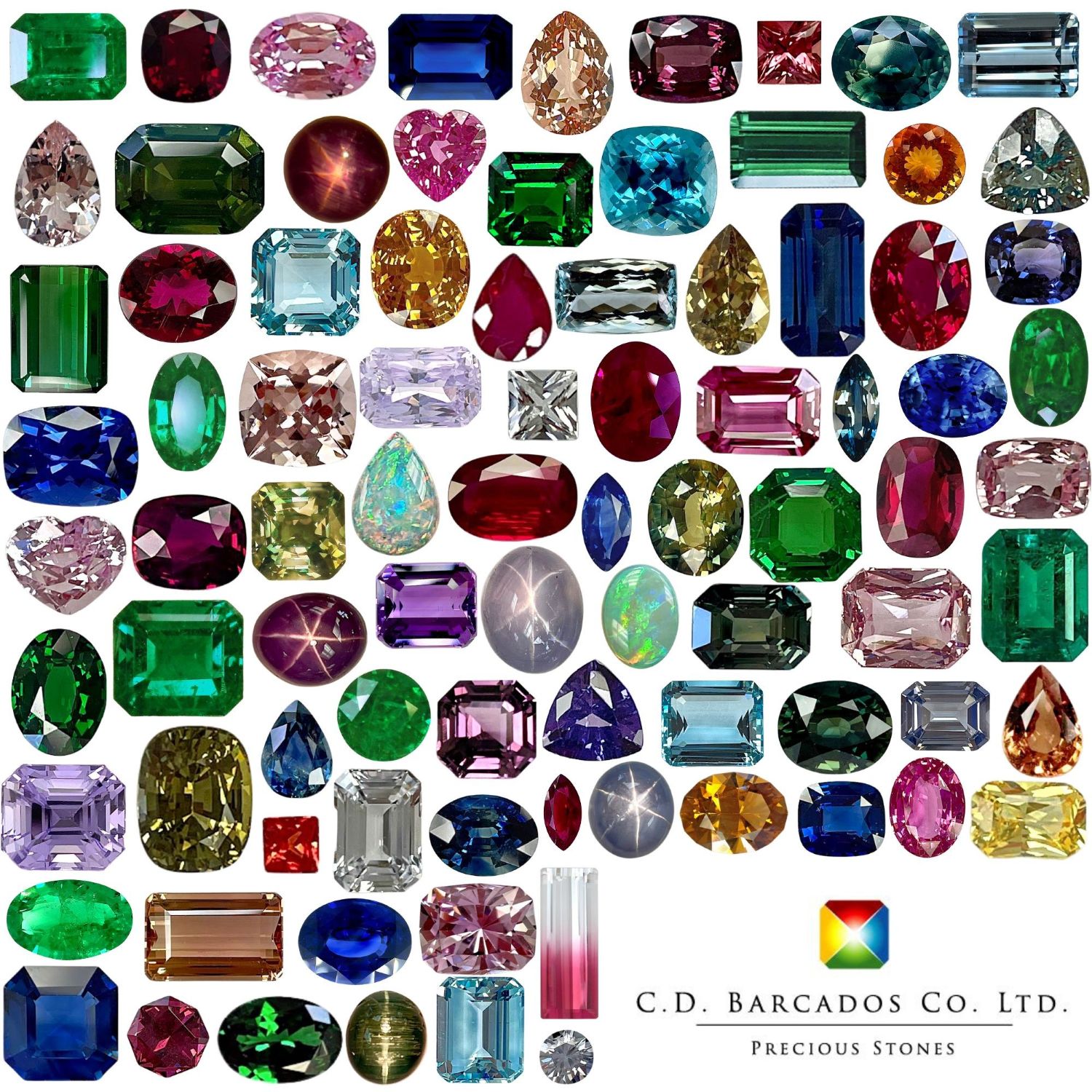

Alex Barcados, of C.D. Barcados in Toronto, says he doesn’t sell any tourmaline as simply paraiba without a discussion on the implications of origin. “Being able to explain the significance of the origin and the confusion surrounding the term ‘paraiba’ is part of our responsibility to our clients,” he says. “If the stone is mined in Brazil, we make it clear this adds value in the market. If it is not mined in Brazil, we explain the significance on its value. If copper is present and we feel the colour would qualify under the LMHC guidelines, we ensure the client is aware of the geographic implications on price. We also use the term ‘cuprian tourmaline.'”

Lisa Elser, a gem cutter based in Vancouver, shares her experience: “When I buy in Africa, no one can guarantee the rough is cuprian (although they say it is) and it’s not something that can be easily tested in the field. That means paying paraiba prices is silly, as the likelihood of getting it is slim. If it is not paraiba-type, I’ll have paid way too much for regular tourmaline.”

For gemstone buyers like Elser, portable advanced instruments such as visible-near infrared (VIS-NIR) spectrophotometers or X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometers that can test for copper content may come in handy.

Legal issue

Paraiba.com sells tourmaline jewellery and gems using only stones originating from Paraiba, Brazil, and not what it calls “African lookalikes.” Since tourmaline from the Paraiba mine is limited, the value of existing stones has increased over time. In my opinion, using the term ‘paraiba’ to include stones from other sites dilutes the value of those sourced from Mina da Batalha.

Business profits aside, gemmologists themselves are divided on whether gems from African mines—or other mines that might be discovered—should be called paraiba. Sapphires from Kashmir or rubies from Mogok, Burma, for example, command some of the highest prices due to their superior colour, transparency, saturation, and rarity. In my opinion, labelling a ‘velvety blue’ sapphire from Sri Lanka as Kashmir sapphire is misleading, and the same can be said when using ‘Paraiba’ to refer to all neon tourmalines with copper and manganese.