This or that? How lab-grown and natural diamonds differ

by Samantha Ashenhurst | January 13, 2023 2:58 pm

By Alethea Inns

[1]If one thing was made clear at last year’s JCK show, it was laboratory-grown diamonds are, yet again, a hot topic in the jewellery industry. Now more than ever, it is important for retailers to be able to communicate clearly with customers the key differences between laboratory-grown diamonds and their mined counterparts.

[1]If one thing was made clear at last year’s JCK show, it was laboratory-grown diamonds are, yet again, a hot topic in the jewellery industry. Now more than ever, it is important for retailers to be able to communicate clearly with customers the key differences between laboratory-grown diamonds and their mined counterparts.

As consumer awareness of laboratory-grown diamonds grows, and retail jewellers increasingly offer them as a purchase option, it is necessary to remain informed on how to disclose appropriately, as well as how to address any customer questions.

Both laboratory-grown and natural diamonds fascinate gemmologists and scientists. Laboratory-grown options are a feat of human ingenuity and scientific accomplishment, while natural diamonds are a feat of nature, brought to beauty by the humans who have sought them for centuries. Each offer something different! It is necessary for us to understand the ways in which these stones are the same and how they differ to help us explain the value of each to curious and increasingly informed consumers.

1) Definition (i.e. what they are)

Similarities

The mineralogical definition of a diamond is “carbon crystallized in the cubic crystal system.”

In this way, laboratory-grown and natural diamonds are the same. These similarities translate to their properties, which we will look at next.

Differences

At the subatomic level, there are essential differences diamond scientists rely on which allow us to separate diamonds by growth origin type (i.e. natural or laboratory-grown). These differences will be explored in the ‘Detection’ section below.

[2]

[2]2) Properties (i.e. how they are described)

Similarities

Following mineralogical definition, because both laboratory-grown and natural diamonds are the same definite chemical composition with the same ordered atomic structures (cubic), their optical, physical, and chemical properties are the same.

Optical

Optically, the two varieties have the same brightness (brilliance), dispersion (fire), scintillation (sparkle), and lustre if their cut and 4Cs are comparable. This is because both have the same refractive index and transparency.

Refractive index indicates how much the speed of light is reduced when travelling through a diamond. The higher the refractive index of a material, the more it slows down light. The more light is slowed down when travelling through a material, the more it must change direction and bounce around internally (i.e. within the diamond) before returning to the eye. This is what gives diamond its characteristic optical properties.

It is the unique structure of carbon atoms within a diamond which give it highly refractive properties. The way a diamond is arranged and the number of atoms per unit volume gives it a high refractive index, which slows down light. Both laboratory-grown and natural diamonds are 99.95 per cent carbon in the cubic crystal system, which means they both have identical optical properties when it comes to interaction with light.

Physical

Like its optical properties, a diamond’s physical properties are a result of the structure of its internal carbon atoms and electrons. Because the outermost shell of each carbon atom has four electrons shared with four other carbon atoms (known as a covalent bond, which has high bond dissociation energy—that is, the amount of energy required to break the particular bond in a mole of molecules), the atoms form extremely strong chemical bonds, resulting in a rigid, strong crystal. This is why diamond has a hardness of 10 on the Mohs scale, and also what gives it a high relative density (what gemmologists call ‘specific gravity’).

Chemical

At room temperature, both laboratory-grown and natural diamonds do not react with any chemical reagents, including strong acids and bases. This is, again, related to their chemical composition and crystal structure. (These similarities are also why a diamond tester will not distinguish the two.)

Differences

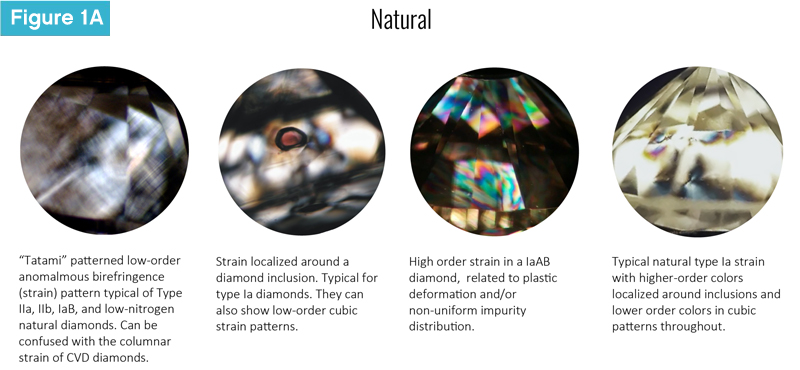

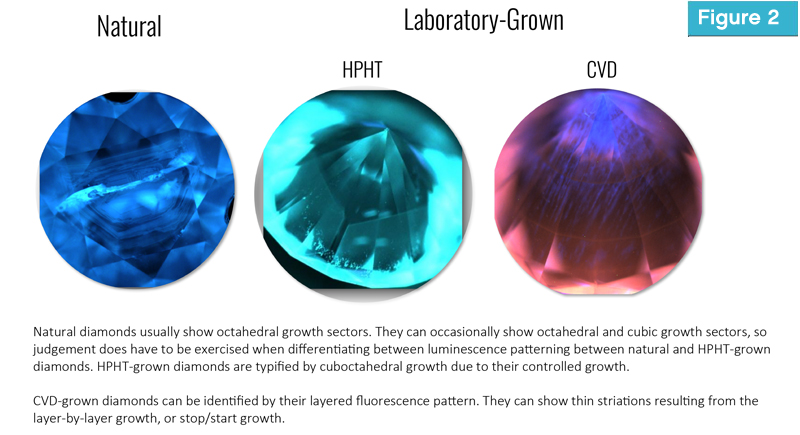

To the unaided eye, there are no differences between laboratory-grown and natural diamonds. This is a function of the properties themselves not being able to be measured by the naked eye. Through standard gemmological testing, however, one may notice a difference in strain patterning, which is observed using cross-polarized light (Figures 1A, 1B).

Strain occurs when, during formation, a diamond’s crystal experiences a physical stress whereby external forces and/or deformation modifies a crystal’s normally isotropic (i.e. cubic) properties.

Natural diamonds are usually subject to varied stress during their million-to-billion-year formation and through their process of transport to the Earth’s surface. Because of natural diamonds’ non-uniform conditions of growth, they typically exhibit a few different types of strain based on their formation, including strain around inclusions, dislocations created during crystal growth, mechanical damage, plastic deformation (like the cross-hatched ‘Tatami’ growth in Type IIa diamonds), or differences in concentrations of impurities.

While the causes of strain are similar for diamonds created using high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) methods, they present differently. HPHT diamonds are grown in a uniform high-pressure field, which means they will often have little or no low-order (desaturated) strain.

Diamonds grown using chemical vapour disposition (CVD), however, are different. Due to their layered, start/stop growth, they show structural strain, which can be observed at the different growth layers and interfaces. Additionally, CVD-grown diamonds often have a higher-order (i.e. more brightly coloured) columnar strain pattern (banded or parallel) due to their growth.

So, does that mean one can use strain to differentiate laboratory-grown and natural diamonds? In short, unless you have seen several thousand diamonds under crossed polars, no. Even in those circumstances, the difference would not be definitive without additional confirmation tests. Strain patterning can overlap between laboratory-grown and natural diamonds, so using it as a singular, definitive confirmation test of growth origin is not recommended.

[3]

[3]

3) Growth (i.e. how they form)

[4]Everything about a diamond is determined by how it forms. From its chemistry to its morphology to its 4Cs, formation is everything. This is also what enables diamond scientists and gemmologists to tell them apart. Understanding growth mechanisms of both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds is important to knowing the properties and their respective similarities and differences.

[4]Everything about a diamond is determined by how it forms. From its chemistry to its morphology to its 4Cs, formation is everything. This is also what enables diamond scientists and gemmologists to tell them apart. Understanding growth mechanisms of both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds is important to knowing the properties and their respective similarities and differences.

Similarities: HPHT diamonds

HPHT diamonds are created as their name implies—under immense pressure and heat. These stones are grown in an environment similar to the Earth’s upper mantle (where diamonds form in nature).

In facilities which grow HPHT diamonds, equipment (i.e. presses) will apply pressure and conduct heat to dissolve carbon so it precipitates from the temperature gradient as a diamond crystal. While there are several designs for these presses, they all operate on the same principle: mimicking the thermodynamic conditions in nature where diamond forms, with the addition of a molten metal solvent (i.e. flux), which acts as a catalyst to enable the carbon to dissolve and act as a transport media. Carbon atoms diffuse through the molten flux toward the slightly colder section of the chamber to form a diamond crystal on the seed.

Differences: CVD diamonds

As its name implies, chemical vapour deposition involves a chemical reaction inside a gas-phase (vapour) as well as deposition onto a substrate surface. Unlike HPHT, CVD crystal growth does not mimic the natural conditions of diamond formation. Instead, a chemical vapour of carbon is deposited on a seed crystal at high temperature. The environment inside a CVD apparatus is a small fraction of one atmosphere of pressure, which means it does not require the high-pressure conditions of the HPHT process.

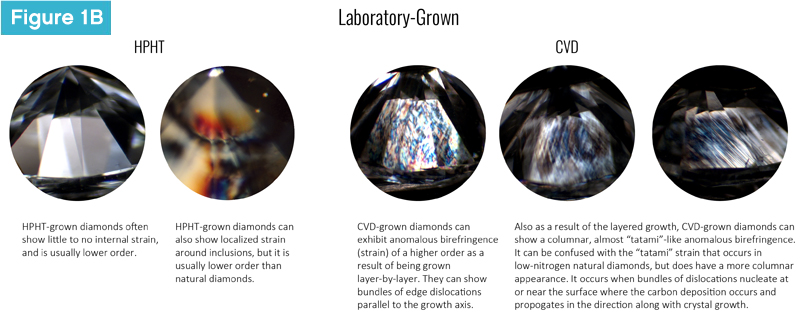

Inside a CVD chamber, carbon-based gases (commonly methane) and other reactant gases, such as hydrogen or oxygen, are added to the environment, and heated to about 800 to 1200 C. The heat causes the gases to break apart and release their carbon atoms, which precipitate onto a diamond-seeded substrate. This release of carbon builds layer upon layer of diamond at speeds of a few micrometres per hour. This growth helps diamond scientists distinguish CVD-grown from HPHT-grown and natural diamonds (Figure 2).

Another factor which aids in the screening and detection of laboratory-grown diamonds is their age. Natural diamond formation spans millions up to billions of years, can be discontinuous, and subject to the heterogeneity of the Earth’s mantle, where they are formed. Laboratory-grown diamonds, however, have the luxury of being formed in uniform, controlled environments.

HPHT methods can take between a few days to a few weeks to grow a one-carat diamond (but averages about two weeks), while CVD growth takes about a month to produce a one-carat diamond. Generally, the longer the growth process, the better the colour and clarity of the laboratory-grown diamond. This is not the case for natural diamonds, where growth time does impact quality, which are rather subject the geology of their growth.

4) Detection, screening, and differentiation

Given laboratory-grown diamonds are able to be created in a span of weeks and natural diamonds can take billions of years to form, there are inherent differences at the subatomic level which enable diamond scientists to differentiate the two. This is where detection and screening and the role of advanced gemmology come in.

Similarities

[5]

[5]Regarding diamond type, there is some crossover, as both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds can be Type IIa, Ib, or IIb[6].

Specifically:

- Type IIa diamonds have no detectable nitrogen, which is typical of HPHT-grown diamonds, as well as natural diamonds formed very deep in the Earth’s mantle.

- Natural varieties with Ib (i.e. single nitrogen) usually indicate diamonds that came to the Earth’s surface shortly after formation and have not had time to ‘cook.’ Meanwhile, laboratory-grown diamonds incorporate nitrogen into their crystal structure from our atmosphere.

- Type IIb diamonds are blue diamonds with boron impurities. The element can be found in a diamond of any growth origin.

Other impurities like silicon and nickel can be found in both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds, but are typically in different concentrations. These impurities have different features and are extremely rare in natural diamonds.

Differences

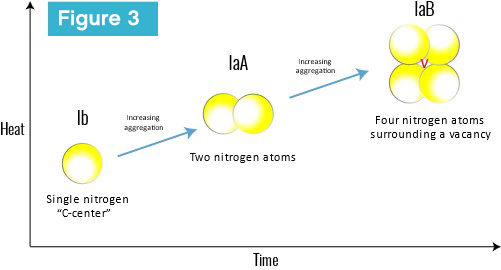

Gemmologists use diamond age to separate natural from laboratory-grown varieties. There are certain processes that happen over billions of years (under incredible heat and pressure) which simply cannot be replicated by humans to date. This is where knowledge of diamond type comes in handy.

With time and heat from being in the Earth’s mantle, nitrogen—the most common impurity in diamond—in its basic, isolated, single form eventually aggregates into more complex defects, including the IaA and IaB aggregates, which are part of the Type I category (Figure 3).

Another nitrogen aggregate in natural diamond that forms along with the others (IaA and IaB) is the ‘N3 center,’ which is the most common naturally occurring aggregate. This consists of three nitrogen atoms surrounded by a vacancy and needs a minimum of a few million years to form. This is why laboratory-grown diamonds are not Type Ia; natural diamonds with aggregated nitrogen (Ia, including IaA and IaB) have taken 900 million to 3.2 billion more years to form than their laboratory-grown counterparts.

Fluorescence and phosphorescence

The N3 center causes blue fluorescence in diamond. When this fluorescence is high enough in intensity, diamonds are very likely high in nitrogen. This is because of the N3 center, which requires billions of years to form in the Earth. This time-specific necessity is why we have yet to see the N3 center in laboratory-grown diamonds.

It is important to note, though: just because a diamond does not fluoresce, this does not mean it is laboratory grown. Likewise, just because a diamond does fluoresce (even blue!), this does not mean it is natural. Gemmologists use the wavelength and intensity of the fluorescence to tell them what the naked eye cannot see (Figure 4).

5) The 4Cs

Similarities

[7]Natural and laboratory-grown diamonds can span a range of colours, clarities, and cuts.

[7]Natural and laboratory-grown diamonds can span a range of colours, clarities, and cuts.

The presence and absence of inclusions does not definitively indicate its grown origin. While many inclusions are distinctive of natural diamonds (i.e. included crystals, twinning wisps) or laboratory-grown diamonds (i.e. black ‘comet-like’ inclusions, metallic growth remnants), there are still some visual similarities where a gemmologist may mistake one for another.

In terms of colour, diamonds of any growth origin can be found in a range of hues along the D to Z spectrum and fancy colours, too. In fact, the cause of colour in fancy-coloured diamonds is usually similar between natural and laboratory-grown varieties. Blue diamonds, for instance, are often caused by boron or irradiation. Orange and yellow varieties are commonly the result of single nitrogen atoms, while green diamonds are typically caused by irradiation and/or annealing.

Finally, cut is dependent on the manufacturer—diamonds of any origin can be any cut.

Differences

When it comes to clarity, most laboratory-grown diamonds fall in the VS range, though this may shift as growth processes evolve and consumer demand changes.

Natural diamonds exist in different clarities, with the majority on the market being in the SI range. Distinctive inclusions (i.e. metallic growth remnants, non-diamond carbon) distinguish laboratory-grown from natural diamonds but rely on a level of expertise by the gemmologist.

Near colourless HPHT diamonds often have what is called a ‘blue nuance’ due to the boron in their structure. These are Type IIb or have a slight yellow hint due to trace amounts of single nitrogen.

Meanwhile, CVD diamonds often show a brownish or greyish cast, related to optical defects in the growth process. This is likely related to nitrogen-vacancy complexes or graphite. CVD diamonds are often decolourized after they have been grown. This requires a high-pressure heat treatment, which can be detected by gemmological laboratories.

Some fancy colour mechanisms have not yet been replicated in laboratory-grown diamonds. Fancy violet diamonds caused by hydrogen impurities and ‘chameleon’ varieties that change from greyish-brownish-green to orangey-yellow upon heat or being kept in the dark, for example, are unique to natural diamonds.

Colour zoning can also differ between growth origins, as this can follow the growth patterning.

There exists a wide range of colours created with laboratory-grown diamonds; colour alone is not diagnostic in determining in if a diamond is natural or laboratory grown.

Conclusion

The physical and optical properties of natural and laboratory-grown diamonds are essentially identical. Differences come into account when one considers the age of the diamond and its growth environment. These are the two keys that enable gemmologists to distinguish the varieties.

Knowing these differences and similarities is vital for success at the sales counter, enabling jewellery professionals to answer questions and provide the relevant information to help consumers make informed decisions. With the rapid expansion and continued growing demand for laboratory-grown diamonds, gemmological laboratories’ reports and services have become essential for retailers to be protected at the point of sale—particularly when it comes to disclosures. Identification of laboratory-grown diamonds requires gemmological laboratories to stay abreast of growth processes and technologies as they evolve.

As a retailer, it is your responsibility to know exactly what you are selling and disclose it transparently and accurately. There is no better way to establish your credibility than to be able to talk about the similarities and differences between natural and laboratory-grown diamonds confidently.

[8]Alethea Inns, BSc., MSc., GG, is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA). Her career has focused on laboratory gemmology, the development of educational and credentialing programs for the jewellery industry, and the strategic implementation of e-learning and learning technology. Inns is chief learning officer for Gemological Science International (GSI). In this role, she leads efforts in developing partner educational programs and training, industry compliance and standards, and furthering the group’s mission for the highest levels of research, gemmology, and education. For more information, visit gemscience.net[9].

[8]Alethea Inns, BSc., MSc., GG, is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA). Her career has focused on laboratory gemmology, the development of educational and credentialing programs for the jewellery industry, and the strategic implementation of e-learning and learning technology. Inns is chief learning officer for Gemological Science International (GSI). In this role, she leads efforts in developing partner educational programs and training, industry compliance and standards, and furthering the group’s mission for the highest levels of research, gemmology, and education. For more information, visit gemscience.net[9].

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/crop_-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1-Natural-Strain-Patterning.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1B__2-Laboratory-Grown-Strain-Patterning.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Fig-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/fig3.jpg

- as both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds can be Type IIa, Ib, or IIb: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/diamonds-whats-your-type

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/fig4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Inns_headshot.jpg

- gemscience.net: https://gemscience.net/

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/this-or-that-how-lab-grown-and-natural-diamonds-differ/