Treasures from Down Under

by carly_midgley | December 3, 2018 3:01 pm

By Benedicte and Martine Lavoie

[1]

[1] [2]

[2]

We recently returned from a trip to Australia, the land of opals and kangaroos! There, we had the opportunity to visit several opal mines and had the pleasure of meeting with extraordinary miners, who were generous enough to show us their mines and explain the opal extraction process from A to Z.

Most mines are on private land and are rented to miners as concessions. These lands are extremely arid and mostly used for livestock. All the miners we met proved to us their work relies on patience, determination, and a certain dose of madness.

Years in the making

Opals need extremely special conditions and millions of years to form. The following is a very brief and simplified overview of these gems’ formation—a process beginning in river waters that flowed when dinosaurs still lived on Earth.

This river water, already rich in silica, would flow on sandstone beds. With gravity, the water-and-silica solution was deposited in cavities in the form of a gel, and the water slowly evaporated. The remaining silica, transformed into miniature spherules of about 150 to 700 nanometres in diameter, became trapped in the cavities. (This is why opals are often found in the form of nodules or horizontal ‘veins’ corresponding to ancient riverbeds and inland seas.)

If the silica-rich molecules form into regular spheres and ordered rows, the light diffracts, which produces a colour scheme. If they are simply deposited in no order, the result is the common opal or ‘potch,’ which forms without any colour scheme. The largest (and much less common) spherules produce red colour sets, while smaller ones produce purples and blues. Black opals showing red and orange flashes are rarer and thus tend to be more expensive.

[3]

[3]It takes all kinds

The world of opals is vast and captivating. A wide variety of opals can be found all over the world, but those of Australia are the most well known and most often used in jewellery. About 95 to 97 per cent of opals on the market[4] are Australian.

Other countries (such as Ethiopia, Brazil, Mexico, and Honduras) also produce small amounts of opals, but Australia is the primary source of the black variety. South American opals are often more orangey (known in the market as fire opals), while Ethiopian opals have more transparency. However, they also absorb a lot of water, which makes them less stable and more prone to cracking than the Australian material. Some other countries, like the United States, Ethiopia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Mexico, and Indonesia, also produce very small quantities of black opals.

White opals

Of the precious opals (i.e. those with a colour scheme), white opals are the most common. In Australia, they are found southwest of Brisbane. The base of the opal ranges in tone from white to very light grey.

White opals have been the best-known variety commercially since the early 1900s. With the many legends surrounding this gem combined with its affordable price point, it is no surprise it’s making a comeback with young designers.

[5]

[5]Black or ‘dark’ opals

Black opals are found at Lightning Ridge in New South Wales, Australia. They can be discovered all along the ridge, which is about 100 km (62 mi) long. The colour scheme of the black opal is particularly noticeable because of its dark background, which contrasts with colour flashes. These are the most expensive opals in the world, as well as the rarest.

However, the Canadian market for black opals is quite weak. Typically, people know much more about the white versions. In our experience as gemstone suppliers, when we say ‘black opal,’ customers tend to react with confusion, especially when we discuss price. In our business, people who ask to buy a black opal know about them and are aware they are rare and expensive.

[6]

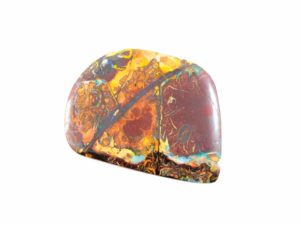

[6]Boulder opals

Boulder opals are found in ironstone. Unlike black and white opals, which are entirely made of opal, these gems are carved from ironstone, because the precious material is often found in veins or layers too thin to be extracted from the rock. They tend to be larger and less expensive than the black variety, although their colour scheme is very dramatic with their relatively dark background.

Boulder opals are much easier to sell in Canada than black opals. They are more affordable, and designers love to use them in jewellery. They are also a little easier to work with, as the ironstone in the back is stronger than the opal itself.

Matrix opals

Matrix opals are like small veins found in ironstone. Their formation is essentially the same as boulder opals’, but occurs in thinner veins (actually fissures filled with silica).

Matrix opals can be both very affordable and very pretty. Just about every market can be reached with these gems and their vivid, colourful veins, and they are a nice introduction into the market of black opal. The blue and green colour seen here is more popular than red and orangey hues, which makes this variety easier to sell.

Opalized fossils

Since opals form inside porous material, some can be found in bone or shell fossils or in fossilized wood. These are usually kept as specimens by collectors.

[7]

[7]Opal country

Opals are found throughout Australia, with different regions producing different types. We had the chance to visit several distinct areas during our trip.

Lightning Ridge

Lightning Ridge is a town located 743 km (461 mi) southwest of Brisbane, Australia. Its economy is mainly based on mining, opal sales, and tourism. Indeed, many Australian tourists visit this region during winter. There, boundary rider Jack Murray found the first black opals in the year 1900.

Lightning Ridge opals are found at a depth of about 6 to 18 m (19 to 59 ft), often very close to the contact zone between the sandstone on the Earth’s surface and the clay below it. Each miner there is entitled to two concessions of 50 x 50 m (164 x 164 ft), which can be renewed each year.

Once the miner has found a location, he or she has 28 days to study the ground before leasing the concession. The miner analyzes the soil by digging samples up to 10 m (33 ft) deep. Once the concession is finalized, he or she digs a hole about 20 to 30 m (65 to 98 ft) deep by about 1.5 m (5 ft) in diameter. The miner carries down equipment as the hole gets bigger and typically installs vertical pine trunks to solidify the mine.

Crushed rocks are vacuumed up to the surface through a large tube, then loaded directly into a truck. At the end of the day, the miner unloads the truck in what is called an agitator (an old mixer truck or cement mixer). The rocks rotate slowly for two to five days in water, which dissolves clay and sandstone. When the process is finished, only common and precious opals remain.

Yowah

A town of 50 permanent residents located about 1000 km (621 mi) from Brisbane, Yowah is where one can find the ‘Yowah nuts.’ These are opals found in ironstone ‘nuts’ the size of a small avocado.

When the ironstones are sawed in two, opals are discovered either in their centres or in the form of veins. Their formation was a mystery until geologists discovered these rocks once used to be more porous, thus allowing silica-laden water to enter.

[8]

[8]On our visit to Yowah, we had the pleasure of meeting opal artist Eddie Maguire, who was kind enough to show us a great part of his collection. Most of the time, the gems in his art are simply sawn in half to show their exceptional beauty and placed on a custom carved wooden base.

Like boulder opals, Yowah opals are rarely completely extracted from the source rock. In these ‘nuts,’ matrix opals can also be found.

Quilpie

One of the most significant parts of our trip was visiting a mine belonging to opal producer Eric Stelzer, located about two hours from the town of Quilpie and accessible only by a bumpy dirt road.

We had the chance to stay at the mine, which produces boulder opals, for two days. This was the first open-sky opal pit we visited, as most of them lay underground. Miners know how deep the opals are, fairly close to old riverbeds.

Just like in Lightning Ridge and Yowah, the soil at this mine is mainly sandstone and clay; one can spot ironstone boulders trapped in the ground. Miners will typically break a few on the spot to see their potential before bringing larger amounts to the camp. Often, they can already notice some veins of colours.

On the second day of our stay at the mine, Eric took advantage of the presence of his son Colin, who is a geologist, to probe another mine about 45 minutes away. With the help of a drone, they were able to take pictures of the topography of the place.

A new perspective

It was amazing to see the full process behind opal mining in Australia. Most miners we met took care of all aspects of mining by themselves, which meant they needed to be very versatile, with the ability to take on different roles. A miner might play the part of mechanic when the truck is broken, engineer when it comes to planning the underground mine and solidifying the walls, businessperson when selling rough or cut opals, and many more.

We also came to realize most miners polish their own rough. They might keep a rough piece for months or even years before they know how it will be cut and which part of the stone will be put in the spotlight.

[9]Benedicte Lavoie, FGA, is co-owner and vice-president of Pierres de Charme and specializes in fine coloured gemstones. She joined the family business after completing a bachelor’s degree in business and human resources (HR) management and was awarded the internationally recognized title of Fellow of the Gemological Association of Great Britain (FGA–Merit). Based in Montréal, Pierres de Charme supplies fine gemstones to jewellers, goldsmiths, and award-winning artists across Canada and the United States. Benedicte can be reached via e-mail at info@pdcgems.com.

[9]Benedicte Lavoie, FGA, is co-owner and vice-president of Pierres de Charme and specializes in fine coloured gemstones. She joined the family business after completing a bachelor’s degree in business and human resources (HR) management and was awarded the internationally recognized title of Fellow of the Gemological Association of Great Britain (FGA–Merit). Based in Montréal, Pierres de Charme supplies fine gemstones to jewellers, goldsmiths, and award-winning artists across Canada and the United States. Benedicte can be reached via e-mail at info@pdcgems.com.

[10]Martine Lavoie, FGA, is president of Pierres de Charme, a company specializing in the sale of gems and precious stones. She founded the company in 2012. With more than 30 years of business experience, Martine has been able to contribute her talents as a dynamic entrepreneur with a sound knowledge of gemmology and jewellery appraisal to Pierres de Charme. In 2016, she was appointed the International Colored Gemstone Association’s (ICA’s) ambassador for Canada. Martine can be reached via e-mail at info@pdcgems.com.

[10]Martine Lavoie, FGA, is president of Pierres de Charme, a company specializing in the sale of gems and precious stones. She founded the company in 2012. With more than 30 years of business experience, Martine has been able to contribute her talents as a dynamic entrepreneur with a sound knowledge of gemmology and jewellery appraisal to Pierres de Charme. In 2016, she was appointed the International Colored Gemstone Association’s (ICA’s) ambassador for Canada. Martine can be reached via e-mail at info@pdcgems.com.

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/7.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/6.jpg

- 95 to 97 per cent of opals on the market: http://www.opalauctions.com/learn/news/opal-trends-worldwide-2017

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/8.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/10.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/24.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/bene.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/L2S2H-54QWR8A_LavoieM_03.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/treasures-from-down-under/