Two gemstone treatments you should know about

by charlene_voisin | June 1, 2012 9:00 am

By Hemdeep Patel

The old adage stills seems to hold true when it comes to the jewellery industry—the more things change, the more they stay the same. As the industry grows and adapts to transformations in the day-to-day business cycle resulting from new technologies, products, and information, we are continuously faced with the seemingly insurmountable challenges of gemstone and diamond treatments. Specifically, I’m referring to their physical characteristics and limitations, as well as their disclosure to the buyer. This last point impacts the jewellery industry on three main fronts—at wholesale, during manufacturing, and at the retail level. The effects are loss of money, but at the retail level, this most often results in a damaged reputation and possible litigation.

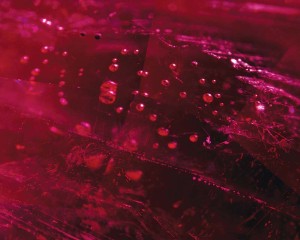

Last December, six U.S. laboratories and trade organizations issued a news alert that lead glass-filled rubies without proper disclosure were making their way into the market. In addition, the rubies carried no information on how to care for them to maintain their appearance. Although similar warnings have been issued in the past, what was interesting about this one was the fact the stones are being sold at prices near that of untreated or conventionally treated rubies of the same size and colour. Previously, the low price of a lead glass-filled ruby was a clear indicator of its true nature.

Keep in mind this warning was issued by trade members in the United States, where litigation and enforceable fines can quickly resolve these issues in the consumer’s favour. In contrast, Canada is quite unique in this respect, since there are no such laws. Instead, it is up to owners to make customers aware of their business practices regarding disclosure of treatments. This can range from full disclosure to none.

The issue of lead glass-filled rubies has been around for the last decade, and the core problem of the treatment has always been the level of disclosure. For many gemmologists and knowledgeable jewellers, identifying this treatment is quite easy, but it has been the correct classification of these stones and the disclosure of the physical characteristics of the lead glass filling that has been lacking. In fact, to call this a treatment might also be misleading, since a ‘treatment’ implies something has been made better or improved while maintaining the original gemstone. This could easily mislead consumers to believe they are purchasing a ruby with some additives to make the stone better. In the vast majority of cases, filling can comprise more than half the stone’s total volume. In fact, if one could remove the lead glass filling, the ruby would be negligible in total weight. So it might be more accurately called ‘lead glass filling with ruby.’ As such, a number of gemmological laboratories refer to these stones as a composite ruby, made up of lead glass and ruby. For its part, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) feels this term does not accurately reflect the extent to which the ruby is treated, and prefers instead to use the term ‘manufactured product’ in its reports without any reference to ruby or corundum.

The second part of this issue—which by far is most important for those selling undisclosed composite rubies—continues to be educating the consumer of how to keep the treatment intact. A consumer wearing a filled ruby might be shocked to see their stone has discoloured after coming in contact with lemon juice or any number of household items. Providing this information can easily be done by either educating sales staff of the stone’s physical properties or providing the customer with detailed instructions on how to care for it.

Coating the truth

A new addition to our ever-growing list of treatments brings to mind another adage: what was old is new again. In this case, I’m referring to the application of a foreign substance to a gemstone or diamond.

Diamond and gemstone coatings have been around for more than a century and were initially devised to impart or enhance a unique colour onto a stone. If one wanted to make a yellow sapphire or diamond look more intense, that could be accomplished by adding colour to the stone along the culet or girdle in the same hue.

Today, this coating treatment is experiencing a comeback in the form of diamond-like carbon (DLC) applied to gemstones and cubic zirconia. The treatment involves applying a thin coat of DLC ranging from 5 to 50 nm (1 nm is 0.000000001 metre) through one of several methods.

The DLC coating imparts some important physical properties, such as increased hardness, improved wear resistance, and a reduction in surface friction. In the case of stainless steel, for instance, an application of DLC roughly 1 μm thick (i.e. 0.000001 mm) can increase the lifetime of a low-impact piston from one week to one year. If the application’s thickness were doubled, the lifetime would increase from weeks to well over 50 years.

The key factor determining the effectiveness of a DLC application is the quality of the coating. Although there are several coatings that can be classified as DLC, there is a wide range of ‘recipes’ at equally varying costs.

All DLC coatings comprise a few principal ingredients: carbon (in both diamond crystal and graphite form known as sp3 and sp2, respectively), hydrogen, and a wide range of metals. Therefore, the amount of sp3 present determines the purity of DLC and how it is graded.

The second part of the recipe is the method of application. These can range from chemical vapour disposition (CVD), where a carbon atom is precipitated out of plasma onto a surface, to physical vapour disposition (PVD), where charged sp3 and sp2 particles adhere to a surface through an electrical field. (There are several other processes that we can leave out of the discussion for now.) The common factors to all the processes is that the application of the DLC coating is even and, if possible, converts sp2 carbon into sp3 diamond crystal.

Overall cost of application is determined by these two factors, since it is a diamond crystal’s physical properties that are desired, as opposed to that of the graphite. To be effective, therefore, the DLC material must have a high concentration of sp3-formed carbon. It is this form of carbon that costs more.

In order to yield a high concentration of diamond crystal, the method used may be a combination of many different technologies and processes. In addition, they would eventually be determined by the industry and its needs.

Prices can vary greatly, given the range of possibilities where the resulting appearance is concerned and what the industry dictates. More importantly, the DLC coating’s durability is also a consideration. The main problem is determining what kind of DLC coating has been used, since all treatments carry the same diamond-like carbon identification. This creates a significant amount of confusion among consumers and retailers who are unfamiliar with the material. In addition, it is likely manufacturers will come to market with newer economical methods of applying a DLC coating, such as a diluted treatment that uses a lower concentration of diamond crystal in the recipe or a less energy-intensive method of application.

In recognizing this fact, engineers in Germany were able to mandate that all DLC-coated products related to their industries follow distinct classification standards based on the concentration of sp3 carbons and the application process used to adhere the coating to a product.

Preserving meaning

So what does this all mean to the jewellery industry? Simply put, the retailer needs to be informed and knowledgeable, since DLC-coated products are readily available over the Internet and can now be found at jewellery trade shows. Manufacturers claim the coatings increase scratch resistance and that light-behaviour properties are similar to diamond. In addition to the discussed physical properties DLC would impart onto gemstones, treaters say coated cubic zirconia can be indistinguishable from a diamond when examined with the naked eye.

The problem arising in our industry is the word ‘diamond’ is quite valuable. We use it to identify something that is better. For example, a diamond-cut sapphire is not cut to the exact faceting style of the description it carries, but we use that adjective to identify a stone with single facets running from the girdle to the culet. And so when a treated product can be identified as diamond-like carbon, or commonly described as ‘diamond coated with DLC,’ the emphasis is on the ‘diamond’ and less on the ‘like carbon.’ Further, the term ‘DLC’ can be an inappropriate statement when the method used has resulted in a very diluted diamond crystal concentration. Instead, the term ‘graphite-like carbon’ might be more appropriate.

Specific tools and techniques exist for identifying the underlying gemstone treated with a DLC coating. In most cases, however, it can be as simple as using a CZ tester when identifying a cubic zirconia or having a good grasp of what natural gemstone inclusions look like when viewed under magnification. It is important to keep in mind that most consumers looking to purchase an engagement ring or any other diamond product start their search on the web. There are many online e-retailers successfully selling diamond-coated cubic zirconia with full disclosure, which obviously serves a far better purpose. But for many consumers, a DLC-coated cubic zirconia can serve as a very good substitute, since the product carries the moniker ‘diamond,’ and in the jewellery industry, this term is as good as gold. Compared to a similar product sitting in your showcase for thousands of dollars, the appeal of a DLC product at a significantly less cost may be too tempting to pass up.

I’m always looking for interesting developments in the world of gemmology to discuss. If there is something specific you’d like to hear more about, drop me a note.

Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3-D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and GIA alumnus. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at contactus@hkdlab.ca or sales@creativecadworks.ca[1].

Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3-D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and GIA alumnus. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at contactus@hkdlab.ca or sales@creativecadworks.ca[1].

- sales@creativecadworks.ca: mailto:sales@creativecadworks.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/two-gemstone-treatments-you-should-know-about/