Wedding rings and a theory of evolution

by Samantha Ashenhurst | May 7, 2019 10:14 am

By Kate Peterson

[1]

[1]“A ring so destined to encircle the finger of a beauteous girl… A ring having no worth other than the love of the giver.”

~ Ovid (43 BC – 17 AD)

Most who work in the jewellery industry are familiar with the story of the first documented diamond ring used to signify engagement, presented by Archduke Maximilian of Austria upon his betrothal to Mary of Burgundy in 1477. The ring as a symbol of love and commitment, however, traces its history to the earliest days of humanity. Indeed, the tradition of the ring itself and what it represents—a circle with no beginning and no end, with its centre providing a window to the future and its placement on the third finger of the left hand, touching Vena Amoris, the ‘love vein’ that travels directly to the heart—is known by historians to have originated with the very beginnings of humankind.

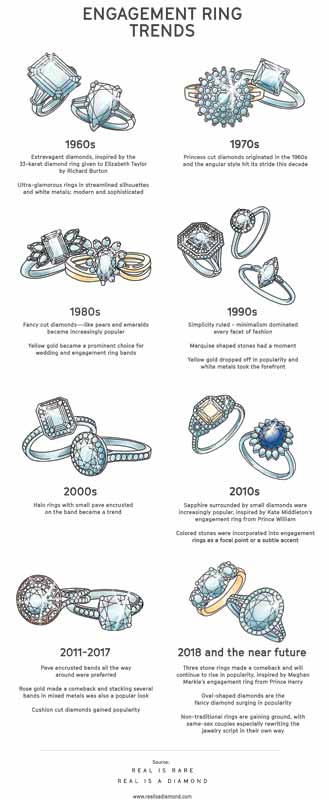

[2]While much has remained constant in regards to bridal jewellery over the centuries, a great deal has also changed, with some of the most dramatic shifts being felt in recent years. Transformations in consumer attitudes and interpretations, combined with changes in everything from style and material preferences, to distribution channels and accessibility have created an environment for retailers that is far less stable than predicted.

[2]While much has remained constant in regards to bridal jewellery over the centuries, a great deal has also changed, with some of the most dramatic shifts being felt in recent years. Transformations in consumer attitudes and interpretations, combined with changes in everything from style and material preferences, to distribution channels and accessibility have created an environment for retailers that is far less stable than predicted.

To understand the role of the wedding ring in our society today, and envision its continuing significance with consumers of tomorrow, it is important to understand the history and evolution of symbolism, style, and materials of these pieces from the earliest days and moving forward. For jewellers, the ability to remain relevant to bridal consumers now and in the future might well depend on our ability to apply the lessons of evolution to modern design, marketing, and retail execution.

Evolution through history

In the earliest days of civilization, a bond shared by two people was often illustrated through a reed or branch, which was tied around a finger, wrist, or waist with a knot to symbolize binding. These knotted rings and bands were thoughts to ward off evil, keeping a couple safe in their union. Historians who study Ancient Egypt have recovered images of gold bands on fingers drawn onto papyrus scrolls that tell the stories of couples and families. At the time, gold was reserved for the wealthy, as it was thought to be the substance of sun or the flesh of the gods. Options for the less opulent included bone, ivory, silver, and leather.

The concept of the ring and its accompanying symbolism was further popularized in the Roman Empire, when large bands were fashioned with a ‘key’ type extension to indicate the promise of marriage. These pieces, which were often made of brass, bronze, or iron, were generally not worn on a finger, but instead suspended from a chain, hung from a hook, or attached to a belt. Even at that time, engraving imparted power to the object; historians in Egypt discovered a key ring[3], dating back to third-century Rome, inscribed, Accipe Dulcis Multis Annis (“Take this, sweet one, for many years”).

By the Byzantine Empire in the seventh century, a ring placed on the third finger of the left hand had become the unmistakable symbol[4] of commitment and love.

[5]

[5]Later on, the 14th and 15th centuries saw the dawn of many of the wedding ring customs we still treasure today. Among these traditions are the construction of precious metals, engravings on the inside of a ring, the symbolism of a diamond, and the use of coloured gemstones (primarily ruby, sapphire, and emerald), which were believed to have mystical powers.

Further, betrothal rings for women (often thin bands set with diamonds or gemstones) came to represent a marriage contract between families. Because these bands were costly and precious, a ‘keeper’ ring was often placed over the top of the betrothal ring to ensure that the band was not lost. By the late 1800s, these rings had evolved to resemble modern engagement rings, with the ‘keeper ring’ becoming the wedding band, similar to how we know them today.

Styles and norms continued to evolve through modern times, with wide variations in materials (e.g. metal, enamel, diamonds, gemstones) and custom pieces. While precious metals (i.e. gold, silver, platinum, and palladium) remained consistent, esthetic shifts, like the rise of the Art Nouveau period (1890 – 1910), as well as historic events that limited availability, such as the First World War (1914 – 1918) and the Second World War (1939 – 1945), raised the demand for alternative, unique materials.

In what might be considered a return to those days, as well as to times as far removed as Ancient Egypt, an increasing number of today’s bridal couples are choosing to make a personal statement with rings made from a variety of metals and other components, including steel, titanium, ceramic, iron, bone, leather, carbon, and even rubber.

| HISTORIC INSIDE-RING ENGRAVINGS |

| Posey rings, dating back to the 15th century, offer insight to the origin of modern inside-ring engravings.

In the 1400s, the power of the written word, especially in the form of poetry, was very significant. Artifacts from the period show some of the loving inscriptions and genuine sentiments of the time:

Other interesting finds shed light on some 15th century humour:

|

Evolution of diamond symbolism

[6]

[6]Dating back to biblical times, diamonds have represented an integral part of human experience, often posing as the ultimate symbol of confidence, achievement, and the purity and strength of love. These gemstones have a rich history as family treasures with powerful emotional value that is able to reach across generations, symbolizing connections between loved ones and the celebration of shared experiences. It is said that diamonds make the intangible tangible; thus, it should be no surprise the diamond remains a hallmark of commitment and marriage in modern culture.

While the emotional connection to the diamond engagement ring has remained constant through centuries, the material symbolism shifted with generations. In the 15th and 16th centuries, for example, the diamond was considered part of the marriage contract, serving as a price paid for the hand of the bride. Later, while still part of the ‘contract,’ the diamond was considered the holder of the promise a man offered to his betrothed. For most, this promise was tied to the diamond’s intrinsic properties—purity permanence—and not to its size or cost. By the mid-20th century, diamonds were largely positioned as proportionate to love: the bigger the diamond, the greater the representation of a strong and loving relationship. This imagery, however, faded with the baby boomer generation; today, an engagement ring, regardless of its size and gemstone, is seen as a representation of the unique style and message of a specific couple.

Evolution in the millennial market

As has been the case since the 1940s, bridal jewellery is the strongest segment of the current diamond market and is largely driven by a sizable and vocal millennial base. Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, represent up to 24 per cent of the combined Canadian and U.S. population. Contrary to some assumptions, millennials love diamonds just as much as their predecessors, with recent studies indicating this group represents an estimated 41 per cent[7] of current diamond jewellery demand. Further, those within this group are still getting married and continue to look to the engagement ring as a symbol of love and commitment—but on their own terms. For many in this group, the engagement ring represents a couple’s journey together and their present bond, but not necessarily an impending conventional wedding ceremony. In recent years, millennials have done their part to put engagement rings in the forefront on social media, using hashtags such as #Engaged, #EngagementRing, #HePutARingOnIt, and #SheSaidYes. This has generated millions of global posts around every variation of engagements, proposals, and, above all, rings.

It is important to note that, in many cases, the millennial bridal customer is an experienced luxury shopper with an established sense of style. They tend to be more affluent than previous generations, generating a larger income sooner, but marrying later. Today, the average age for first-time brides and grooms[8] in Canada is 29.6 and 31, respectively,4 which means most have developed style and/or brand loyalty for fashion jewellery before they even enter the bridal market. As such, with bridal, as with fashion gifts and self-purchase, these consumers are looking for a personal statement that is representative of their journey. Surveys indicate that, after extensive online research, most modern couples look at two to seven rings in person[9], with their purchases driven primarily by design, lifestyle compatibility, and individuality. Today’s bridal customers are conscious of value, but they do not confuse value with price. Rather, ‘value’ is relative to personal relevance; not cost.

[10]

[10]Nonetheless, diamonds remained the choice of more than 75 per cent of couples[11] engaged in 2018. We have seen a resurgence in the choice of coloured gemstones for bridal jewellery, which perhaps can be attributed to the drive for personal relevance, as well as a significant interest in synthetic diamonds as an alternative to those mined from the earth.

Lower-cost synthetics seem to appeal to consumers who value technology, as well as to those who accept claims of higher levels of environmental and social responsibility as true. Natural diamonds, however, offer the inherent value and authenticity that, for most couples today, better represent their shared message.

“Diamonds and engagement/marriage jewellery share a holy bond,” says Sarah Gorvitz, head of communications for the Diamond Producers Association (DPA). “In 2017, the DPA surveyed 1500 millennials and, while some make other choices (i.e. alternative jewellery, experiences), the majority still want—and choose—diamonds for bridal. More than 40 per cent vow they would never buy a synthetic engagement or wedding ring, regardless of cost.”

While there is currently a great deal of debate within the jewellery industry between natural diamond advocates and proponents of synthetics, the clear message from consumers is that accurate information and transparency are essential for retailers who are hoping to maintain a position of integrity in the market.

Materials and customs have followed many cycles in their evolution over centuries, but the ring that signifies love, bond, and commitment—the circle with no beginning and no end, with an open window to the future—remains one of the most compelling of human symbols. If history is the standard, it will also serve as the key that affords jewellers the privilege of sharing in some of the most significant moments in their customers’ lives for centuries to come.

[12]Kate Peterson is president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Performance Concepts, Inc., a firm offering retailers staffing, business development, management, and performance solutions. Peterson is a regular contributor to JCK and Instore Magazine and a sought-after speaker at trade events such as JCK, American Gem Trade Association’s (AGTA’s) GemFair, and the JA New York show. She can be reached via e-mail at kate@performanceconcepts.net[13].

[12]Kate Peterson is president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Performance Concepts, Inc., a firm offering retailers staffing, business development, management, and performance solutions. Peterson is a regular contributor to JCK and Instore Magazine and a sought-after speaker at trade events such as JCK, American Gem Trade Association’s (AGTA’s) GemFair, and the JA New York show. She can be reached via e-mail at kate@performanceconcepts.net[13].

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/opener-5.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/crop1.jpg

- discovered a key ring: https://www.langantiques.com/university/roman-jewelry/

- the unmistakable symbol: https://brewminate.com/the-history-of-a-byzantine-engagement-ring/

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/crop_whitegold.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Engagement-Rings_Infographic.jpg

- represents an estimated 41 per cent: https://www.brides.com/story/millennials-buying-diamonds

- the average age for first-time brides and grooms: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/marriage-and-divorce

- look at two to seven rings in person: https://go.weddingwire.com/newlywed-report

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/crop_gold.jpg

- more than 75 per cent of couples: https://go.weddingwire.com/newlywed-report

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Peterson_headshot_crop.jpg

- kate@performanceconcepts.net: mailto:kate@performanceconcepts.net

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/wedding-rings-and-a-theory-of-evolution/