What makes ethical jewellery ethical?

by carly_midgley | August 3, 2018 9:42 am

By Marc Choyt

[1]

[1] [2]

[2]

I like to tell people I got my MBA in Haiti, where I volunteered for two years in the ’80s after college. There, I ran an orphanage and worked in Mother Teresa’s clinics in shantytowns, holding babies and bandaging cancers. It’s not that I took business courses, but that I learned life lessons that shaped my business outlook.

As business partners, my wife and I are both keenly concerned about social justice and environmental sustainability. We have always questioned what others take for granted.

According to Amnesty International, about 3.7 million people have died in wars funded by diamonds, yet we still see zero restitution, truth, or reconciliation. (For more details, click here[3].) Millions around the world are being poisoned by mercury from gold mining, destroying the environment just so they can scrape by.

The truth is the talismanic symbolism of jewellery is too often disconnected from its sourcing. Why must it be this way, and what can we do about it?

A rising wave

[4]

[4]Concerns over human rights and sustainability in relation to jewellery have been growing for the last 20 years, since Global Witness exposed conflict diamonds.

I remember the crowds attending panels on the Blood Diamond film when I was showing in JCK Las Vegas’s designer section in 2006. I myself attended Martin Rapaport’s session on fair trade diamonds. Ultimately, diamond sales were not impacted, mainly due to the Kimberley Process (KP), which was established in 2003.

Since then, the notion of ‘conflict-free’ has extended beyond diamonds to include both gold and coloured gemstones. Additionally, there are many environmental concerns. As one example, Earthworks and Oxfam introduced their No Dirty Gold campaign in 2004. Today, when I mention the term ‘dirty gold’ when I’m selling wedding rings, my customers get it.

[5]

[5]According to the De Beers 2016 Diamond Insight Report[6], 36 per cent of millennials, when purchasing a diamond wedding ring, are unlikely to compromise on the question of responsible sourcing. They research multiple online channels, can sniff out fake narrative, and will use their dollars and social media to express their values with one click of a mouse.

Certainly it is better to be in front of the wave, ahead of these paradigm shifts, than behind. However, developing a truly ethical sourcing platform is not as simple as it might seem.

Ethical jewellery 101

Let us, for a moment, imagine a piece of jewellery that—even in its sourcing and fabrication—represents our noblest and most heartfelt values. What would that mean, in practice?

These days, the general notion of ‘responsible jewellery’ is based upon the concepts of ‘chain of custody’ and ‘traceability and transparency.’ Essentially, that means the transactions that take place between the mining of a metal or gem and its purchase by the final customer are tracked. Jewellers use some variation of these terms when marketing their products, in a “from the mine to your finger” narrative. Yet, how ethical is the chain of custody approach?

Diamonds

Though the ‘conflict-free’ narrative is as powerful as ever to the public, the transparency-focused Kimberley Process has been largely discredited by independent watchdogs, including Global Witness and IMPACT, two organizations originally involved in forming the scheme. The custody approach only tracks rough diamonds and does not take into account human rights or ecological concerns.

The Canadian diamond sector provides a great alternative. In the northern territories, when mines are on Indigenous lands, Impacts and Benefits Agreements (IBAs) made between mining companies and tribal governments are standard. IBAs ensure First Nations people gain financial benefit from the extraction. Plus, the Canadian government has stringent environmental regulations for mining sites. However, the polishing operations of some of these companies are not so transparent and are still treated as ‘trade secrets.’

Another consideration is the fact a worker in a Canadian mine might make more in a day than an African miner makes in a month, despite the fact African countries need diamonds for development. (For more information, click here[7].)

Gold

[8]

[8]When it comes to large-scale gold mining, which forms about 80 per cent[9] of global supply, companies often mine in several locations or countries. A mine in a developing country may not adhere to standards anywhere near what we would expect in Canada.

Yet, the chain of custody approach typically treats all the gold mined by one company as equal. Environmental and human rights issues can be bypassed at a mine located in a country where standards are weak or nonexistent.

Therefore, a certification scheme that relies entirely on chain of custody has questionable ethical veracity. Additionally, there are other critical reasons why we might question the chain of custody approach: past actions.

If companies were people

[10]

[10]Suppose you were assaulted and robbed. If the criminal was allowed to argue a few years later that your complaint was in the past and therefore invalid, civil society would break down. Why shouldn’t we hold businesses that work within civil society to such standards?

If you Google a major, multinational mining company in the context of human rights and the environment, you will most likely discover major concerns from nongovernmental organization (NGO) watchdogs. If a company has committed past transgressions, shouldn’t that company have to acknowledge its faults and create some program for reconciliation and restitution as a foundation for any new assertions of ethics? I think the answer to these questions is yes.

Unfortunately, when ‘chain of custody’ simply means a company currently has control of its mined product from mine to market, the ethical standard may have no impact on practices on the ground, and meeting it might be as simple as drafting some paperwork.

Similarly, blockchain—the latest technical chain of custody solution—can also fail to address labour and environment issues, as well as potential impact on Indigenous people. It favours the large-scale mining operations where profit does not stay local, but is exported to shareholders.

Matters of chain of custody, traceability, and transparency are all foundational to ethical practices, but true ethical jewellery must have one other main feature—a focus on small-scale mining communities.

Artisanal small-scale mining

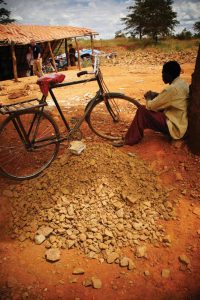

Small-scale diamond, gold, and gemstone miners need beneficial economic development to feed their families. In an ideal scenario, money stays local, and the people on the land gain maximum benefit from their resources. However, that is not easy, because it requires the industry to source from the small-scale mining sector.

[11]

[11]Large-scale mining contributes 7 million jobs globally, while the latest research tells us 150 million people across 80 countries depend on small-scale mining. (For more details, click here[12] and here[13].) Women comprise 25 to 50 per cent or more of small-scale miners. (More information is available here[14].)

Worldwide, 20 per cent[15] of gold comes from small-scale miners, which are the largest contributor to global mercury after coal-fired power plants. Small-scale miners also produce about 20 per cent of diamonds and the vast majority of coloured gemstones. This type of mining is characterized by exploitation, poor and unsafe working conditions, child labour, and extreme poverty. It occurs informally, and often in countries with marginal civil society institutions.

For jewellery to be truly ethical, a jeweller should be able to confirm his or her purchase from these miners is actually maximizing benefit to their local economy. Small-scale gold miners—who are sometimes paid in sacks of dirt—would, in a truly ethical system, have access to international markets instead of selling to middlemen who can take 30 per cent of the value. They would also be trained in how to mine in a socially and environmentally safe manner.

Ideally, standards and principles are needed to back up the veracity of an ‘ethical’ claim in support of a strong local economy. In the context of gemstones, for example, there would be cutting facilities increasing beneficiation. Legions of NGOs are currently ‘capacity building’ with small-scale mining communities, but the greatest progress—particularly in terms of the consumer market—has been fairtrade gold.

Gold in the United Kingdom

[16]

[16]Fairtrade and fairmined gold started out as one standard, a joining of two organizations (Fairmined and the Fairtrade Foundation) back in 2011. The two split in 2013, and have become competitors.

In the United Kingdom, which has the most developed market for small-scale ethical gold, the choice has been Fairtrade. More than 250 small jewellers have joined the Fairtrade gold commercial program, and the bridal market has been particularly strong. The U.K. trade magazine, Professional Jeweller, named fairtrade gold a major market trend in 2017, while fairmined gold was not even mentioned. (To read the article in question, click here[17].)

One of the main reasons for this is Fairtrade is one of the most respected global brands. Consumers also respond to the independence of the label. Fairtrade is not invested in the jewellery industry any more than in coffee or chocolate. It functions to set up commercial platforms and an auditable system between jewellers and miners, and funds its programs with a fee of $2.30 per gram of gold at retail.

With Fairtade, miners not only get technical assistance, but are also paid 99 per cent of international spot price and an additional social premium of $2000 per kilogram. Premiums have been used to fund schools, clinics, and elder care, as well as reinvested in mining operations. Fairtrade helps communities that were once marginal start to thrive.

In the United Kingdom, at least, where suppliers have integrated fairtade gold into mill and casting products, the additional cost of a fairtrade wedding ring might amount to only $40. That isn’t much for the story you can tell your customer, who is purchasing the most precious gold in the world.

Unfortunately, in North America, neither fairtrade or fairmined gold have landed as market forces. A big reason for this is the prominence of recycled gold.

Gold in North America

Originally, the use of recycled gold (branded by Hoover and Strong back in 2007) was a positive step forward the trade could take in response to the No Dirty Gold campaign. Over the last few years, numerous brands have adopted recycled metals to back their ‘eco-friendly’ stances.

However, compared to fairtrade gold, using recycled metals has no impact on mining whatsoever. Gold is used as an investment. Whether large-scale gold mining takes place depends on the amount of gold per tonne of rock and spot price. Hoover and Strong, which has always been at the forefront of ethical gold, now carries fairtrade gold in addition to recycled.

A jeweller who really wants to make a difference for small-scale miners has to seek out individual suppliers who understand the relationship between small-scale and jewellery. It is a process that can take time and market testing. While some very successful companies have made ethics the centre of their unique propositions, my experience as a pioneer in ethical retail indicates the product, first and foremost, has to be well priced and designed. Ethical sourcing acts as a ‘halo effect,’ defining the values of a company while differentiating it from its competitors.

Moral veracity

[18]

[18]Having seen the suffering resultant from extreme poverty in my youth, I see connections others might not. It is difficult to forget witnessing small-scale miners in Kenya mixing gold and mercury with their hands, then burning off the mixture in frying pans before cooking their dinners.

Soon after my wife and I started our company, we launched a restoration project of a creek that had been damaged by decades of over-grazing. I thought, “The revenues from my company—from gold that could have been purchased from miners destroying part of the Amazon watershed—is being used to repair this river near my home.”

How to conduct business knowing all of life is intertwined is an ongoing question I live with as I read about ice caps melting and oceans dying. We need to protect and preserve all life-generating systems for future generations. Certainly, looking for opportunities to align our economic decisions with broader environmental and social concerns is one of the most immediate and potentially impactful actions we can take.

We can’t just think about tomorrow, or next week. It’s about our children, and children’s children. It’s also about daring to think big and ask the question, “What’s our 500-year plan?”

[19]Marc Choyt is president of Reflective Jewelry[20], a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He is also the only certified Fairtrade gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery, which were often executed through Fair Jewelry Action, a campaign network that focused on ecological and human rights concerns. His upcoming e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds[21], will be published online in late summer. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifest or via e-mail at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

[19]Marc Choyt is president of Reflective Jewelry[20], a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He is also the only certified Fairtrade gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery, which were often executed through Fair Jewelry Action, a campaign network that focused on ecological and human rights concerns. His upcoming e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds[21], will be published online in late summer. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifest or via e-mail at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Designs-from-Reflective-Jewelry-made-with-fairtrade-gold-and-recycled-silver.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Miner-in-Tanzania-mixing-mercury-and-gold.jpg

- here: http://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/68000/pol300022007en.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/A-mercury-retort-that-separates-mercury-from-gold-safely-photo-by-author.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Small-scale-mine-in-Tanzania-aiming-for-fairtrade-gold-certification-photo-by-author.jpg

- De Beers 2016 Diamond Insight Report: http://www.debeersgroup.com/en/reports/insight/insight-reports/insight-report-2016/millennial-trends.html

- here: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/world/africa/25diamonds.html

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Small-scale-miner-with-a-gold-in-quartzite-5-by-7.jpg

- 80 per cent: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DSC05919-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/engagement.jpg

- here: http://www.mining.com/rising-mineral-prices-trigger-artisanal-small-scale-mining-explosion-report

- here: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining

- here: http://grow.research.mcgill.ca/publications/working-papers/gwp-2017-02.pdf

- 20 per cent: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PHOTO-E.jpg

- here: http://www.professionaljeweller.com/10-things-jewellery-industry-learned-2017

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DSC05871.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Marc-Choyt-portrait.jpg

- Reflective Jewelry: http://www.reflectivejewelry.com/

- Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds: https://reflectivejewelry.com/ethical-jewelry-expos%C3%A9

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/what-makes-ethical-jewellery-ethical/