Synthetics crafted in minutes at room temp lab

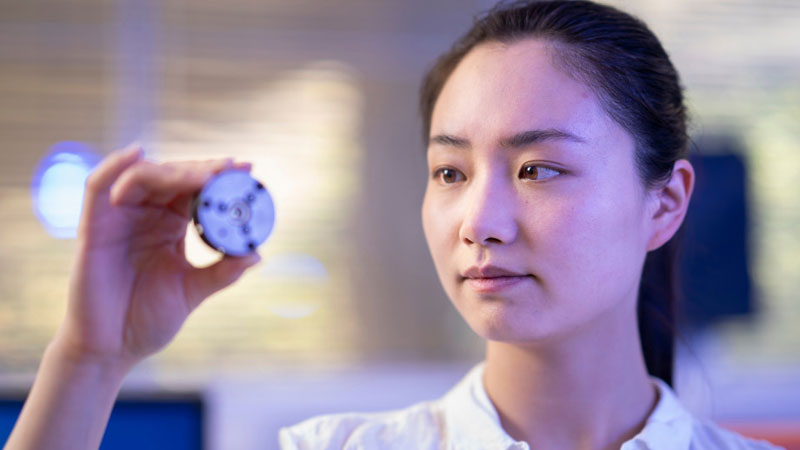

Photo by Jamie Kidston, courtesy ANU

Applying pressure equivalent to 640 African elephants balanced on the tip of a ballet shoe has allowed an international team of researchers to create synthetic diamonds in a room-temperature lab within a matter of minutes.

The feat is a grave departure not only from natural diamond formation—which typically takes billions of years and occurs deep within the earth at temperatures greater than 1000 C—but also from more traditional processes required to make diamonds in labs (i.e. high pressure, high temperature [HPHT] or chemical vapour deposition [CVD]).

Led by researchers at the Australian National University (ANU) and RMIT University, the scientists created two types of diamonds: one traditionally used in jewellery, and Lonsdaleite, which is found in nature at the site of meteorite impacts, such as Arizona’s Canyon Diablo.

While the team had previously created Lonsdaleite, this was only achieved while working at high temperatures; the ‘unexpected’ new discovery, ANU says, shows these diamonds can also form at normal room temperatures by applying only high pressure.

“The twist in the story is how we apply the pressure,” says Jodie Bradby, PhD, a professor from the ANU Research School of Physics. “As well as very high pressures, we allow the carbon to experience something called ‘shear,’ which is like a twisting or sliding force. We think this allows the carbon atoms to move into place and form Lonsdaleite and regular diamond.”

The ‘regular’ diamonds, researchers say, form within the veins of the Lonsdaleite. They were identified through advanced electron microscopy techniques used by co-lead researcher Dougal McCulloch, PhD, and his team from RMIT.

“Our pictures showed the regular diamonds only form in the middle of these Lonsdaleite veins under this new method developed by our cross-institutional team,” he says.

“Seeing these little ‘rivers’ of Lonsdaleite and regular diamond for the first time was just amazing and really helps us understand how they might form.”

Lonsdaleite has a different crystal structure to regular diamond, and is predicted to be 58 per cent harder, researchers say.

“Lonsdaleite has the potential to be used for cutting through ultra-solid materials on mining sites,” Bradby says.

“Creating more of this rare but super useful diamond is the long-term aim of this work.”

The findings have been published in the journal Small.